Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

I settled back into my hermetic life. I spent my days in bed, writing. After a few days, I began to fear I would never hear from Édmonde again. I considered returning to the manor where she'd lodged me, but I realized I had no idea of how to find it on my own. When her letter finally arrived, more than a week after we'd parted, it was on plain paper, with no letterhead or return address. The envelope appeared to have been tampered with, as if opened with the aid of steam and resealed. The landlord, I suspected, hoping to find money inside. Édmonde had thought of this: we'd agreed to write to each other in a kind of code, impenetrable to outsiders.

Dear Charles, her note read,

Forgive me that this letter has taken rather longer to reach you than I would have wished. I am making every effort to find the person matching your description. Even under normal circumstances, arranging such a meeting would prove troublesome, but my physiognomic impediment only adds to the difficulty. You asked me to find an able-bodied youth with literary talent. I have made my tour of the city's universities and seminaries and have unearthed no such personage. I shall now venture further out, into the provinces and towns, and shall write to you as soon as I have found a candidate. Please remain patient and hopeful. Yours, etc.

Three days later, Édmonde's next missive arrived. It, too, betrayed signs of having been opened illicitly. Take the nine o'clock train to Charleroi on Tuesday. I will meet you there.

* * *

Standing beside the ticket counter at the village railway station, Édmonde, veiled as always, appeared to be the dark center of the revolving world, impervious to the noisy, smoky hubbub that overtakes a railway station in the moments after a train's arrival. But when she spotted me limping toward her (I was still walking with a cane), she sprang into action. She took me by the arm and led me outside, through the clatter of horses, buggies, and drivers, to the village coffee house. "His name is Fernand Roux," she said. "He is exactly what you asked for—young, educated, from a family of clerics. He is healthy, afflicted neither by the pox nor by consumption. And he is a seminarian. After his ordination, he wants to travel to the colonies to convert the natives."

"What does he know of our intent?"

"Only that your soul needs saving," she replied. "Which is not untrue." We entered the coffee house. Édmonde looked about a moment and, still gripping my forearm, started off in the direction of a young man sitting alone at a wooden table. The youth was so gaunt and angular in appearance he reminded me less of a man and more of a praying mantis, with a wispy beard and longish hair carefully arranged to fall over one eye. On account of his unusual height, he had adopted a permanent stooped posture and seemed to be folded into his chair rather than seated upon it. "Bonjour, Monsieur Roux. Allow me to introduce you to my friend, Monsieur Baudelaire."

Roux stood and suddenly towered above me. My eyes reached only his shoulders. We bowed our heads and shook hands. His was clammy and insipid. There was a heavy pause for a moment as I found my kerchief and wiped the hand the seminarian had just held. "Madame Édmonde tells me you are in need of spiritual counsel," the young man finally said, in a high, nasally voice that, I suspected, was intended to sound urbane.

"Quite," I replied, and we fell back into an involuntary silence. I looked helplessly across to my co-conspirator but, as her face was veiled, found no clue of how to proceed. "And you are pursuing religious studies?"

"Why, certainly, I am resolved to serve God's mission in the tropics—life among the savages of the Congo, saving the souls of the cannibals, bringing them into the light of Christ and so forth." He began to describe to me, in a pinched, precious tone, the righteous future that lay before him. The impression his discourse made was not so much of vocation but of vanity, and yet he was completely unaware of his effect. As I listened to him, I began to consider the possibility of inhabiting that elongated body, of speaking in that whine, of using those spindly, spidery fingers for every task, of stooping my head every time I had to pass through a door. The thought of it was not a pleasant one. Would I, in the new body, comb my hair the same way? Would I speak with the same insufferable tone? If I retained no memory of my previous existences, and I entered such a body, what kind of fate was it that I was condemning myself to? He, in turn, was completely unaware of the fate that would befall him, were we to execute our designs. He would cross into my body, which teetered on the edge of permanent decrepitude. Such a fate was hardly better than mine. The thought of crossing with the seminarian seemed suddenly obscene.

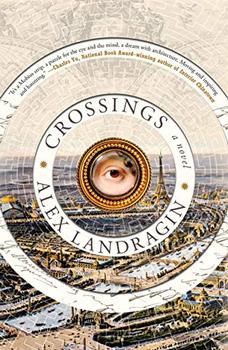

Excerpted from Crossings by Alex Landragin. Copyright © 2020 by Alex Landragin. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.