Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

"Charles?" I heard Édmonde's voice. The youth had stopped talking and must have asked me a question, which, lost as I was in my meditations, I had not heard. I affected a toothache and begged my leave.

When Madame Édmonde joined me outside moments later, I was leaning against the wall of the coffee house, deeply troubled. Once more she took me by the arm and we began walking back in the direction of the railway station. "What is the matter, Charles? Are you displeased with the fruit of my labors?"

"The man is a simpleton, there's no question about it. The thought of a life in that body is unbearable. But there are other considerations: if we were to cross, his soul would die in the misery of my body and, as contemptible as he is, I cannot consent to that, especially if it were to happen without his knowing it. It would feel too much like theft. I would rather undertake no crossing at all, and die and be done with it."

We entered the station's waiting room and Édmonde helped ease me onto a seat. "Charles, you stipulated a man, and not just any man, but a healthy, educated man. Can you conceive how difficult it is to persuade such a person to take seriously the idea that a crossing might be possible? And even if it were done, to then convince him to give his body away, especially for one that is ill and frail? There is not a man in all of Europe who would agree to such a thing." Even from behind her veil, I could sense Édmonde's ire radiating from her. "If you are now insisting that you will only cross with someone knowingly, you have made my task almost impossible. For who will believe such a story? It took you more than twenty years to believe me."

"I cannot agree to it."

"Very well," Édmonde sighed, "I will find someone who wishes for death. But Charles, I beseech you, the streets abound with young women in despair, women whose circumstances are so straitened that to them death seems preferable to life. Think on it."

We parted in disagreement.

On my return voyage to Brussels that same evening, I was at first alone in my compartment. With Édmonde's words still ringing in my ears, the pain of my neuralgia flared as never before. I swallowed an entire bottle of laudanum to dull the aches and entered into euphoric somnolence. When the train stopped at Genappe, two young women entered the compartment. They appeared to be sisters. Upon their entrance, they greeted me by saying, in French, "Good evening, Father." It was not the first time in my life I had been mistaken for a man of the cloth, no doubt on account of my gloomy visage and dark vestments. The two demoiselles sat opposite me and retreated into each other, speaking Flemish. Because I was invisible to them, they were behaving quite naturally. I watched them discreetly, so as not to diminish the spontaneity of their comportment. I sat so that I appeared to be looking out the window at the passing pastures, but as it was dark there was little to see, other than the reflection of the illuminated interior of the compartment. I fixed my attention on the reflection of the two women in the glass and listened to that strange language, which always reminded me of the gurgling of a stream. I studied their femininity—their voices, their movements, the clothes they wore, the intimacy they enjoyed. Surrounded by women every day, I have nonetheless never ceased to be astonished by their strangeness. What is it like, I wondered, to be a woman? What is it like to be able to conceive life? I'd always flattered myself that, as a literary man, I had the imaginative wherewithal to answer the question poetically—and that poetry was my only available means of answering the question. But could writing alone cross the gulf that separates men and women? For the first time in my life I was willing to admit that I doubted it, and from that admission sprang a succession of thoughts that led me, by the time the train arrived in Brussels, to a conclusion diametrically opposed to the opinion I'd held when it had left Charleroi. If a crossing was indeed possible, what did I have to lose by exploring that other manifestation of the great human duality? Woman. Womanhood. Observing those sisters, I was for the first time intrigued by the possibility of such a crossing—by the thought of no longer being imprisoned by the tomb of manhood—the freedom, the release from that dungeon of violence, ambition, and lust! The only person I'd known whose life had been more difficult than mine was Jeanne—and I had contributed mightily to its hardship. I decided I could justify refusing womanhood on no moral grounds other than cowardice.

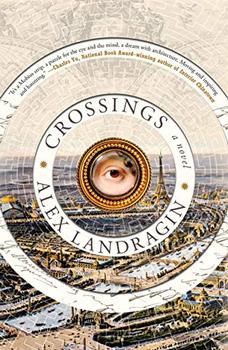

Excerpted from Crossings by Alex Landragin. Copyright © 2020 by Alex Landragin. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.