Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

I paused. My diatribe was garnering some nervous chuckles and an occasional tut-tutting from Madame Hugo. The three ladies in front of me seemed unsure of how they should react—whether this was a performance intended to amuse or injure. Once again I heard a distant plea from Auguste: "Charles, please stop this nonsense." But when in this sort of mood, I cannot help myself.

"There are no women in this country. No women and no love—no gallantry among the males and no modesty among the females. The women are physically comparable to sheep, pale and yellow-haired, with enormous, tallow legs—not to mention the horrors of their ankles. They appear unable to smile, due no doubt to some congenital muscular recalcitrance and the structure of their teeth and jaws—"

"Enough!" This time it was Charles Hugo who interjected, throwing his chair back as he rose to his feet, his face scarlet, his clenched fists visibly trembling with rage. "I will not have my guests humiliated thus!" He threw his napkin on his plate and strode out of the room, which was left in a frosty quiet. The three ladies were blushing crimson, and two of them had tears in their eyes.

"Charles," said Auguste, "please, let us take our leave."

* * *

Auguste offered to accompany me to the Grand Miroir. I expected him to berate me for once again humiliating the both of us with my antics, but instead he packed tobacco into his pipe and smoked it quietly as we walked arm in arm over cobblestones rendered slick by the foggy evening. My nerves were soothed by the closeness of my friend, the fragrance of the burning tobacco, and the night's icy stillness.

As we walked, I put my free hand, tingling with cold, into my coat pocket and felt it rub against soft, thick paper. I stopped and took it out and held it up to the light of a gas lamp. It was a note for no less than one hundred francs, presumably slipped into my pocket by Madame Hugo as we were bidding each other farewell. I was delighted: I would be able to buy more laudanum in the morning. I suggested we go to a tavern and have a drink to warm ourselves. Auguste stopped walking and considered me with an odd look on his face, a look at once loving and sorrowful. "No, my friend," he said, "I think I'll go home to my wife and children." Home. Wife. Children. The words cut me to the quick. If only I was worthy of uttering such a simple phrase. He embraced me and walked away without another word, huddled over in cold and worry. As his silhouette retreated and faded into the dim fog, I saw for the first time the extent to which he, too, was a defeated man, this lifelong friend of mine, my publisher and protector, my staunchest ally and closest confidant. It was evident that he had, without my even noticing it, perhaps without even noticing it himself, joined me among the ranks of the vanquished. There is a mysterious alchemy that overtakes a man when he tastes the bitterness of one of life's definitive routs: a shrinking and a stooping, a seeping away of vital energies, a realization that the best is behind him. While I had been prophesying my own demise my whole life, anticipating it, relishing the foretaste of it, his defeat was still new and unfamiliar to him. His palate was not yet habituated to its flavor. Worse still, I was partly to blame. He'd lost a small fortune publishing my poems, defending them in court when the censor deemed several among them on the subject of sapphic love to be indecent, and then pulping the lot when the trial was lost. As his silhouette slinked away in the pale lamplight of that frigid Brussels night, even the hat on his head seemed smaller, and his shoulders disappeared under the scarf he'd wrapped around his neck.

With Auguste gone, I headed down the Rue des Paroissiens in the direction of the Grand Miroir, turning my collar up against the drizzle. The streets were empty and silent, except for the sigh of burning gas in the lamps and an occasional flurry of footsteps behind me. I slipped on a paving stone and landed with both feet in water up to my ankles.

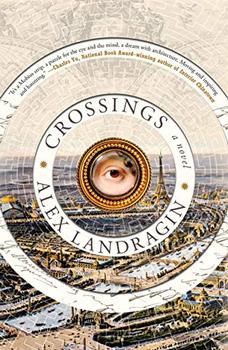

Excerpted from Crossings by Alex Landragin. Copyright © 2020 by Alex Landragin. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

To make a library it takes two volumes and a fire. Two volumes and a fire, and interest. The interest alone will ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.