Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

"Stop it," Cherilyn said, and flipped over the burgers. "I'm fine. I'm serious. I know you have to be excited. Your very first trombone lesson. How'd it go?"

Douglas walked around the stove so she could see him. "Okay," he said, and waved his arm as if painting the scene. "Imagine, if you will," he said, "the sound of an elephant being kicked in the balls."

"Quit that," Cherilyn said. "Did Geoffrey say that to you?"

"No," Douglas said. "Geoffrey's great. It's not him. It's just a little overwhelming, you know. I mean, that man can play twelve instruments. He's a genius."

"Well, so are you," Cherilyn said. "But enough of all this down talk. Let's have some music."

"Your wish," Douglas said, "is my pleasure."

Now, the first thing one should know about Douglas Hubbard is that he has always been, since his youth, an amazing whistler. A true wonder, really. Douglas Hubbard can whistle in any key and at any tempo he desires. The man is like a bird in the forest. He whistles confidently, whistles constantly, yet bothers no one. Not even the slouched-over high schoolers in his History classes, checking text messages beneath their desks. Not even his exhausted colleagues, sitting through another depressing faculty meeting. Not even the testy parents at the grocery store, trying desperately to keep their kids from wreaking havoc on the candy selection. And most importantly, of course, his whistling doesn't even seem to bother his wife, who, for the last twenty years of her life, has been perpetually immersed in the sound of him.

So, when Cherilyn said she wanted some music, Douglas knew where she was coming from and whistled for her "When You're Smiling" by Louis Prima, a man who had been on his mind all day. Cherilyn quietly opened the macaroni and cheese and fiddled with the knobs on the stove and, while he whistled, Douglas walked back to the kitchen table and took his new trombone out of the case. He ran a small cloth over the bell of it and reattached the slide. He handled it as carefully as one does a secret because, for many years, that's exactly what it was.

It wasn't until the night before his fortieth birthday, after all, that Douglas had finally confessed. He began by telling Cherilyn the large and emotional truth, which was that he felt he'd hit a wall in life. He believed it was time to make big-picture changes. Since somber conversations like this were rare in their home, Cherilyn understood he was serious and sat beside him on the sofa. She let Douglas carry on in his self-deprecating and humiliated way without interruption. It had nothing to do with their marriage, he assured her, and he meant it. Yet here he was nearly bald and sporting a comb-over. Here he was soft in his belly. He had recurring and inexplicable pains in his feet if he wore certain shoes. He had no serious hobbies, he realized, no remarkable trophies on their bookshelf, and had made no permanent mark on the world. Each of these depressing observations, as if he had just read them in the papers, appeared to Douglas as undeniable facts. Even his job as a teacher, he told her, the one he now understood he'd likely have forever, was not as fulfilling as it had once been. He'd nurtured no prodigies, rescued nary an at-risk youth off the Deerfield streets, and could barely remember ever even giving a D.

It was, by all means, a crisis.

Then, after he had talked himself out and the two of them put on their nightclothes and crawled into bed, Douglas told Cherilyn the practical truth: that shaving off his mustache to become a hotshot trombonist was all that could save him now. It was what he had always wanted to be, he told her, ever since he'd seen a man playing trombone on the corner of Bourbon and Royal Streets on an eighth-grade field trip to New Orleans and felt, for the first time in his life, a love of music. It was perhaps still the reason he felt so drawn to music, the sound of it live and on vinyl, the jazz and funk masters, even the symphony, as he inevitably imagined himself one day playing those brassy notes when he heard them. And so how was he now forty years old? How had he never kept that promise to himself? To give it a try, at least? To pursue it? How had all those years gone by? With everything else in his life so admittedly happy and secure, Douglas told her, this was his only regret in the world and he could no longer deny it. Life was too short. Time was too precious. Desire was too big. It all made sense to him. He snuggled next to her in the quiet dark after he said this, wondering if she was awake, then wondering if maybe she was asleep, until Cherilyn spoke, and asked him to kiss her with his mustache one last time. After that, she whispered, if he really thought it would help him blow a trombone, she would shave off the push broom herself.

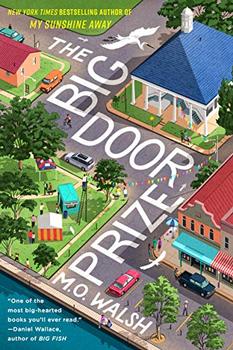

Excerpted from The Big Door Prize by M. O. Walsh. Copyright © 2020 by M. O. Walsh. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.