Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

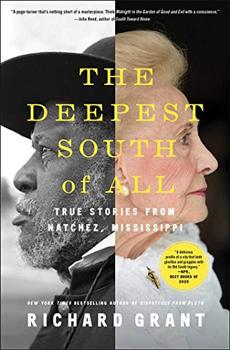

True Stories from Natchez, Mississippi

by Richard Grant

Tens of thousands of people were sold here. They were transported by riverboats up and down the Mississippi. They were marched overland all the way from Virginia and Maryland to the booming new cotton frontier in the Lower Mississippi Valley, of which Natchez was the capital and the epicenter. The men were bound together in wrist chains and neck manacles and forced to march the thousand miles in lockstep. The women were usually roped together and the children put in wagons with the injured and heavily pregnant. These caravans of misery were known as coffles and flanked by men on horseback with whips and guns.

The slaves were told to sing as they marched, to keep up morale, but the coffle song lyrics that survive are mostly sad and mournful, because so many of the people singing had been sold away from their families.

The way is long before me, love

And all my love's behind me;

You'll seek me down by the old gum tree

But none of you will find me

As the coffle neared Natchez, the slave traders would stop and camp for a while. The human merchandise, which had not been unshackled for bodily functions or any other reason for months, was finally bathed, rested, fattened up, and made ready for sale. The women were typically put into calico dresses with pink ribbons at the neck. The men were dressed up in top hats, white shirts, vests, and corduroy velvet trousers. Pot liquor, the greasy residue of vegetables boiled with pork fat, was rubbed into their skin to make it shine. Thus prepared and ordered to "step lively" to encourage their own sale, they were herded into the pens at the Forks of the Road slave market.

Prospective buyers examined teeth, hefted breasts, poked and prodded, leered, mocked, and humiliated in the usual way, but there was no auction block here. Purchasing a human being at the Forks was like buying a car today. You agreed on a price with the dealer, made a down payment, and signed a contract agreeing to make further payments until you owned the property outright. Only the very rich bought slaves without financing.

Considering the volume of suffering and degradation generated here, and the global economic consequences of slavery's expansion into the Lower Mississippi Valley, the richest cotton land on earth, it seemed like such a modest little memorial: a few signboards, a set of manacles, a small patch of mown grass with flowerbeds. Most of the site was occupied by small businesses—a tire shop, a car wash—and low-income housing where all the tenants appeared to be African American, living on the same patch of ground where their ancestors were bought and sold.

I drove on past vacant lots, boarded-up buildings, nice old houses in need of paint and repair, a handsome Gothic Revival church. Then I crossed Martin Luther King Street, which appeared to be the demarcation line between black Natchez and white Natchez, and two different income brackets. Now the old houses were well maintained and freshly painted with attractive front gardens. The downtown historic district, originally laid out by the Spanish in the 1790s, was charming and lovely and from the high bluff there was a spectacular view of the Mississippi River.

Driving around, I saw some of the antebellum mansions for which Natchez is best known. The town and the surrounding area contain the greatest concentration of antebellum homes in the American South, including some of the most opulent and extravagant. Looking at these Federal, Greek Revival, and Italianate mansions, their beauty seemed inseparable from the horrors of the regime that created them. The soaring white columns, the manacles, the dingy apartment buildings at the Forks of the Road, the tendrils of Spanish moss hanging from the gnarled old trees, the humid fragrant air itself: everything seemed charged with the lingering presence of slavery, in a way that I'd never experienced anywhere else.

I parked outside King's Tavern, a two-story building of brick and timber, still recognizable through its restorations as an eighteenth-century tavern. Pushing open a stout wooden door, I came into a low-ceilinged room with heavy beams, exposed-brick walls, and a bar made out of whiskey-barrel staves. Regina Charboneau hugged me like an old friend.

Excerpted from The Deepest South of All by Richard Grant. Copyright © 2020 by Richard Grant. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

To win without risk is to triumph without glory

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.