Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

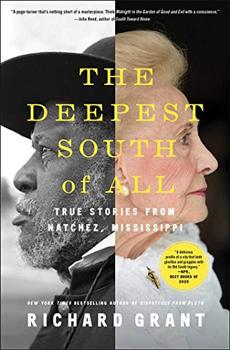

True Stories from Natchez, Mississippi

by Richard Grant

"Yes, we receive visitors in our homes as guests."

"You'll have to excuse my ignorance, but what are hoopskirts?"

"Surely you've seen Gone with the Wind. Those are hoopskirts, like our great-grandmothers wore before the War."

Miss Bettye, as people referred to her, showing respect for her seniority, struck me as the epitome of a grand and gracious Southern lady from a bygone era, and I was amazed to hear that she ran a tugboat company on the Mississippi River with her daughter Carla. "Miss Bettye still goes to work every day except when she's at the beauty parlor," said Regina when I found her on the back gallery. "There's another woman in her nineties who runs a radio station. We've always had a lot of strong, capable, powerful women in this town."

Mansplaining—the tendency of men to interrupt women, hijack the conversation, and explain how things really are—was strikingly absent from this social scene. Women dominated the conversations and interrupted the men, who responded by fading obligingly into the background. Even charismatic big-shouldered oilmen held their tongues. I asked a wealthy genteel businessman how power and social prestige works in Natchez, and he said, "Why on earth are you asking me? We just do what the matrons tell us to do, and for God's sake don't quote me using the word matron."

Regina worked the party, currying favor, placating egos, soothing conflicts, dissolving tensions, gleaning information, hinting at opportunities, applying pressure, asking after loved ones and children. There were important things to do, huge sums of money to raise. For starters, Stanton Hall needed a new roof and other repairs, and that was going to cost the garden club $750,000.

Portraits of the Stanton family stared down from the walls. Frederick Stanton, who built this mansion with enslaved labor, was an Irishman from Belfast who transformed himself into a Southern planter, slave owner, and cotton merchant. Very few of the Natchez nabobs, as the antebellum millionaires were known, were products of the American South. They were outsiders, mostly from Pennsylvania, who quickly mastered the skills of acquiring land and growing cotton with slaves, a system of production that one historian describes as "capitalism with its clothes off."

I tried to broach the subject of slavery with one of the dowagers. "There were no slaves in Natchez," she insisted haughtily. "We had field hands on our plantations, of course, but they were out of town or across the river. Here in Natchez, we had servants and we loved them. They were part of our families."

When I relayed this to Regina, she rolled her eyes, sighed, and said, "I'm sure that's what she's been told her whole life, and some people probably did love their servants and mammies, but those people were owned, they were enslaved, they could be bought and sold, and so could their children. You can't just leave that part out!"

The most surprising thing about Natchez slaveholders is that many of them were Unionists. Even though the local economy was utterly dependent on slavery, Natchez voted not to secede from the Union, predicting accurately that it would lead to a ruinous civil war, and the town surrendered twice to the Union army without a fight. The Natchez planters entertained Union officers in their mansions, and some homes were appropriated as military headquarters. The Union army departed without destroying the town, and that is why so many antebellum homes are still standing in Natchez today.

That night, in my comfortable four-poster bed, I was unable to sleep. My mind swirled with questions. How did Pilgrimage, when the ladies dressed up in hoopskirts and invited paying tourists into their antebellum homes, connect into the Royal Court, the Confederate uniforms, the children's maypole dances, and the social prestige of the mothers? Were any black people involved in this, except as servants?

Excerpted from The Deepest South of All by Richard Grant. Copyright © 2020 by Richard Grant. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.