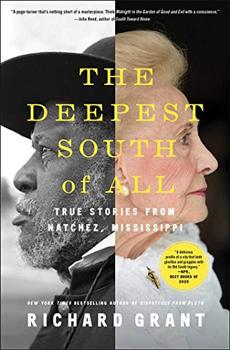

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

True Stories from Natchez, Mississippi

by Richard Grant

And Regina had mentioned "the other club," in a disparaging tone of voice, and Doug had explained that there were two garden clubs in Natchez, and they had been feuding since 1935, although he didn't say why, or how such a thing might be possible. And flashing in and out, as my restless mind raced through the night, were phrases and images from those panels at the Forks of the Road, coffle songs and Negroes! Negroes! in top hats and calico dresses.

I kept coming back to Natchez, and staying at Twin Oaks, for two main reasons. The town is so singular, so fascinating, so richly stocked with bizarre tales, outlandish characters, contradictions and surprises. The mayor, for example, was an openly gay black man named Darryl Grennell. He was elected with 91 percent of the vote in a small, remote Mississippi town that is nearly half white and was once a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan violence. What is this place? I wanted to know. And how did it get this way?

At the same time, I came to see Natchez as a microcosm, or a barrel-strength distillation, of some much larger unresolved issues around race and slavery in America. In most of the country, especially if you're white, it's fairly easy to believe that slavery happened a long time ago and has nothing to do with the current racial situation in America. To sustain that belief in Natchez, however, requires strenuous denial and extra-large blinders because visual reminders of slavery are all over this racially divided town, whose marketing slogan until the 1990s was "Where the Old South Still Lives." These reminders are not just in the antebellum homes with their adjoining slave quarters, and the old slave-market site that you drive past on the way to buy groceries. Some African Americans here can look at their skin tone and know the white person whose ancestor lightened it.

Slavery and its legacy come up in almost every aspect of civic life in Natchez. It is heatedly discussed in meetings of the tourism department and the city council. It is addressed in local theatrical performances, historical reenactments and African American choir recitals. It is tackled at family reunions where black cousins fathered by white ancestors are being invited for the first time. After 150 years of denial and Gone with the Wind fantasy in the white community, a genuine effort is now underway to recognize the role of slavery in the town's history, as the necessary first step before any kind of racial progress can be made.

There was another question that I kept asking myself in Natchez: What was it like to be enslaved here? The local slaveholders left behind a vast trove of letters, diaries, books, and papers, nearly all of it reflecting their self-image as honorable ladies and gentlemen, trying their best to fulfill their paternalistic duties towards their frequently exasperating racial inferiors. But almost nothing exists from the tens of thousands of illiterate people whose labor they exploited and whose lives they essentially stole. A handful of ex-slaves in the area were interviewed by white people in the 1930s, but those interviews, while interesting, are brief and patchy, and many of them were doctored afterwards to present Mississippi slavery in a better light.

Ultimately, there is only one Natchez slave whose life story we know in detail, and that is because it was so extraordinary. People interviewed him and wrote the story down. In Natchez he was known as Prince, and today his portrait hangs on the wall of the mayor's office at City Hall. When I moved into the upstairs rooms at Twin Oaks, I put a copy of the same portrait on the nightstand.

When he sat for the artist, his forehead was deeply lined and his white hair was grown out like a halo. Considering what he had gone through, his face was almost miraculously composed and self-assured, with a look of deep intelligence in the eyes. It's a portrait of dignity against all odds, with an air of royalty still discernible.

Excerpted from The Deepest South of All by Richard Grant. Copyright © 2020 by Richard Grant. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Experience is not what happens to you; it's what you do with what happens to you

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.