Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

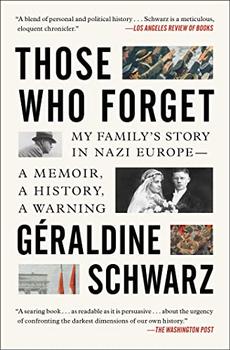

My Family's Story in Nazi Europe – A Memoir, A History, A Warning

by Géraldine Schwarz

I couldn't find a copy of my grandfather's denazification questionnaire, but he must have filled one out, because a letter from the occupation authorities indicates that they knew very quickly of his party affiliation. After Karl Schwarz died in 1970, my father looked everywhere in his papers for traces of the card or for party insignia, without success. As soon as the Allies announced their entrance into Mannheim in March 1945, my grandfather, like many of his compatriots, must have thrown any compromising proof into the kitchen stove along with the Nazi flags that were flown from balconies on national holidays. Who knows, he may have even burned a portrait of the Führer that had once hung, as a safeguard, in his office, or destroyed one that my grandmother had saved in a drawer out of attachment. It was a wasted effort, since the local chiefs of the NSDAP fled the city without even a half-hearted attempt to destroy the registry of Mannheim party members, which the Americans found intact when they arrived.

But Karl didn't clear away his Nazi past completely. In Opa's papers, my father found a very strange heraldic drawing: a knight's helmet on a background of black and gold plants partly shielding an imaginary creature—a cross between a goat and a deer with red horns and hooves, whose neck is pierced by a red arrow. Beneath it, the name Schwarz is written in complex calligraphy, with the date 1612 and this text: "The origins of this bourgeois family whose lines flourish in Swabia and Franconia are to be found in Rothenberg." Under National Socialism, genealogy was very much in vogue and even achieved quasi-official status in the service of the regime, which needed to lend its muddy theories of race a credibility that no serious science could provide. This drawing would have had only decorative value, since joining the Nazi party required a document that was more complicated to establish: a certificate of Aryanism, requiring an extensive number of detailed justifications proving the Aryan origins of the applicant and his or her spouse, at least as far back as 1800. It perplexes me that Karl Schwarz also had this nonrequired crest done in watercolor and ink. By all accounts, my grandfather was not a hardline National Socialist—he was too smitten with liberty. "He might have hung it in the offices of his company, so that whenever a Nazi client or official passed through, they would ask fewer questions and leave him alone," my father said. In the thirties, rumors circulated in Germany about business owners suspected of hiding their Jewish origins, which contributed to an atmosphere of paranoia and accusation so intense that some people even published announcements in the newspapers denying any link to Judaism. Opa destroyed his certificate of Aryanism, but strangely, he spared his watercolor, and kept it until his death. According to my father, "he liked the drawing because it gave the illusion of a glorious ancestry. And my father sometimes had dreams of grandeur." In some ways, Karl Schwarz was a man of his time.

As they faced the scope of the task they'd given themselves, the Americans quickly decided to integrate the German justice system into the process of denazification. After the questionnaires were examined, the people suspected of being implicated were sent to one of a few hundred German arbitration chambers in the American zone. In Mannheim, they sifted through 202,070 forms, 169,747 of which were considered "not implicated." Of the 8,823 Mannheim citizens judged at the German hearings, 18 were classified as major offenders, 257 as offenders, 1,263 as lesser offenders, 7,163 as Mitläufer, and 122 were exonerated. I doubt my grandfather had a hearing. Either way, since the Americans struggled to find "clean" German judges due to the high degree of complicity with National Socialism among legal professionals, and had to resign themselves to recruiting among the old guard, Karl Schwarz wouldn't have had much to fear. Even less so once the occupiers could no longer afford to appear uncompromising while German personnel were urgently needed to deal with the numerous problems confronting their own society: malnutrition, a housing crisis, the lack of coal for heat.… Furthermore, American attention soon turned from former Nazis to focus on a new enemy—the Soviet Union and the Communist bloc. A rigorous start was followed by bungled measures, as the Americans attempted to wrap up the denazification process as quickly as possible in order to accelerate the reconstruction of western Germany, which was on the edge of Communist enemy territory.

Excerpted from Those Who Forget by Géraldine Schwarz. Copyright © 2020 by Géraldine Schwarz. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.