Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

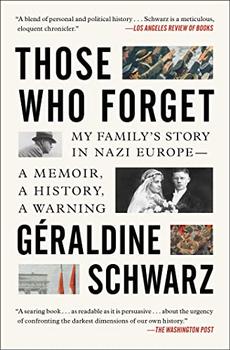

My Family's Story in Nazi Europe – A Memoir, A History, A Warning

by Géraldine Schwarz

In the Soviet zone, which spread across the five easternmost Länder—Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt, Saxony, Brandenburg, and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, as well as eastern Berlin—the denazification measures were applied not only to the Nazis, but also to "undesirables" whom the Soviets wished to get rid of. These so-called Class Enemies included the Junkers, who were the largest landowners, as well as members of the economic elite, social democrats, and other detractors of the new Communist regime, which the occupying authorities quickly tried to put in place following the Moscow model. The Soviets also left the Mitläufer in peace, perhaps because they recognized the opportunity to recycle them into good Communists. However, the more heavily implicated Nazis had more to fear in this zone than in the others, since they could not claim, with the Soviets, to have become Nazi party members to oppose Bolshevism, an argument that carried a certain weight in the West. As a result, many Germans preferred to flee the East, especially because of its infamous prison conditions. Thousands of presumed Nazis and "undesirables" languished in former concentration camps, where at least 12,000 perished. Thousands of others were deported to the Soviet Union, where many of them also died.

In March 1948, the Soviets had already chased more than 520,000 former members of the NSDAP from civil service, particularly from the administration and the judiciary, where they quickly replaced them with "loyal" Communists. In less than a year, these new judges and prosecutors had been "trained," and by 1950 they took on a series of expedited trials called the Waldheimer Prozesse, backed by the authority of the newborn German Democratic Republic (GDR). In two months, approximately 3,400 people accused of committing Nazi crimes were tried, without witnesses and without legal assistance, before these inexperienced judges and prosecutors. Their judgments were determined in advance to obtain the maximum penalty, without distinguishing among Mitläufer, true offenders, or enemies of communism. These phony trials were above all designed to legitimize, after the fact, the internment of thousands of people in special camps. More than half of the accused were given sentences of up to fifteen to twenty-five years in prison; twenty-four of them were executed. Then the GDR decided that the era of denazification was over and threw itself into a long denial of its historical responsibilities in regards to the crimes of the Third Reich, designating the Western Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) as the sole heir to that somber past.

Germans did not support denazification of the population as a whole, which was perceived as an unbearable humiliation, a Siegerjustiz—a conqueror's justice designed to take revenge. But they were largely in agreement with the idea of prosecuting the authorities of the regime.

In November 1945, at the behest of the Americans, a trial opened in Nuremberg against twenty-four high officials from the Third Reich, before an international military tribunal under the authority of the four Allied powers. Treating "the war and the atrocities committed in its name not as politics by other means, but as a crime for which high-ranking politicians and military officers could be held responsible as they could for any other crime" was unprecedented, argues the lawyer Thomas Darnstädt in his 2015 book, Nuremberg: Bringing Crimes Against Humanity to Justice in 1945. The major points were developed in advance in Washington under the direction of Justice Robert H. Jackson. The Soviets, who were afraid of being accused of crimes themselves for the abuses of the Red Army and the nonaggression pact they signed with Hitler in 1939, asked that the international criminal jurisdiction accorded at Nuremberg only apply to Allied powers. Judge Jackson refused: "We are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us." The British, who had their own intensive bombardments of German civilian populations in mind, negotiated a compromise: the rules of criminal conduct would be applied to everyone, but the Nuremberg trials would only be responsible for Nazi crimes. More than two thousand people were mobilized to prepare for the trial, sifting through at least part of the miles of archives left by the ultra-bureaucratic regime.

Excerpted from Those Who Forget by Géraldine Schwarz. Copyright © 2020 by Géraldine Schwarz. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Anagrams

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.