Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

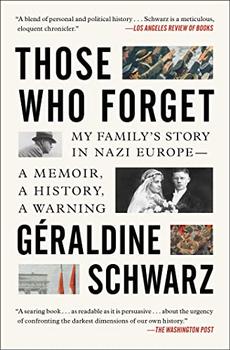

My Family's Story in Nazi Europe – A Memoir, A History, A Warning

by Géraldine Schwarz

A year after the Nuremberg trial opened, the verdict came down: twelve of the accused were condemned to death by hanging, including Hermann Göring, the Reich's second in command; Joachim von Ribbentrop, the minister of foreign affairs; Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the last head of the powerful Reich Main Security Office (RHSA); Wilhelm Keitel, the head of the armed forces high command; Julius Streicher, the founder of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer; and Alfred Rosenberg, ideologue of the Nazi Party and minister of occupied territories in the East. Three were condemned to life in prison, including Rudolf Hess, Hitler's former deputy. Two others—Albert Speer, architect and minister of armament, and Baldur von Schirach, head of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth)—received a twenty-year sentence. Four organizations—the NSDAP, the Gestapo, the SS, and the SD (Security Services)—were classified as "criminal organizations." The judges decided against a petition by the prosecution to include the German General Staff and the Supreme High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) on that list.

The trials demonstrated a resolve, on the part of the Allies, and especially of the Americans, not to let Nazi crimes go unpunished. They defined a new category of wrongdoing: crimes against humanity. But in the short term, these measures didn't have the desired results. Justice Jackson stressed the prosecution of "crimes against the peace of the world" and "conspiracy." This approach reinforced a myth that would take a long time to dismantle: that the Nazi crimes were the result of a secret plan developed by a small group of commanders surrounding Hitler that gave orders to people who were for the most part ignorant that they were participating in a criminal enterprise. Another problem jurists emphasized during the Nuremberg trials was the idea of a tribunal where the victors judged the defeated, imposing silence on the Allied war crimes: the Vichy collaboration; the massive American and British bombardments against German civilians; the atrocities committed by the Red Army in the Reich's eastern territories; the atomic bombs dropped by the United States on Japan. But one of the greatest failures of the trials was to neglect the genocide of the Jews, as this offense did not yet exist. According to Thomas Darnstädt, "even in the face of this incomparable Nazi crime, there was still a taboo in international law against interfering in the 'internal affairs' of a sovereign state," or so the crimes against German Jews were considered. Only crimes against foreign Jews were taken into account, and just after the war, many aspects of the Reich were still poorly understood. Experts had not yet analyzed the proceedings of the 1942 Wannsee Conference, where the Nazi commanders developed their plans for the Holocaust, which by then had already begun.

Between 1946 and 1949, in keeping with the aims of Nuremberg, the Americans organized twelve more trials in their zone in three years, held under their sole authority—bringing more than 185 doctors, generals, economic leaders, jurists, high-ranking bureaucrats, and commanders of the Einsatzgruppen into court. Twenty-four were condemned to death, thirteen death sentences were carried out, and most of the rest received long prison sentences. At the same time, American public indignation in response to the images of concentration camps that had begun to circulate in the press led the United States to create a military tribunal on the grounds of the Dachau camp, to try the personnel of the six camps situated in the American zone. Approximately 1,600 of the accused were condemned, and 268 of the 426 death sentences were carried out.

In the three Allied zones in the West, approximately 10,000 Nazis in total were condemned by German and Allied tribunals. Of those, 806 were condemned to death, and a third of them were executed. These figures reveal a certain effectiveness, considering the amount of time they had. However, many people who deserved imprisonment for their crimes during the Reich succeeded in slipping through the wide loopholes in the net cast by the Allies. To escape, you had only to pass as a Mitläufer by falsifying a few papers and paying one of the Persilschein, those false witnesses to "innocence" or "cleanliness," who were named after Persil washing powder. These witnesses were rarely verified by the occupiers, partly because they were overwhelmed by the scale of the task, and also because their motivation quickly began to flag in the context of the Cold War.

Excerpted from Those Who Forget by Géraldine Schwarz. Copyright © 2020 by Géraldine Schwarz. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.