Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

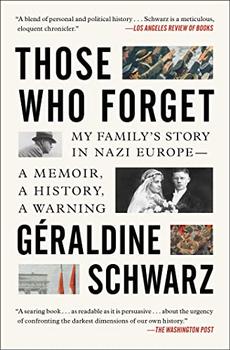

My Family's Story in Nazi Europe – A Memoir, A History, A Warning

by Géraldine Schwarz

One of the largest discredits to the Allied cause was their own conduct in profiting from their position of strength by stealing German technological knowledge. From the beginning of the twentieth century, the spectacular achievements of German scientists were envied the world over. Between 1900 and 1939, thirty-four were awarded a Nobel Prize (fifteen in Chemistry, eleven in Physics, and eight in Physiology or Medicine), a quarter of them to Jewish Germans. During the same period, fourteen French scientists got the prestigious prize, twenty-two British, and seventeen Americans. The Reich's defeat was the chance for these countries to help themselves to the kind of technological expertise they lacked, expertise that was especially important in the context of the Cold War. Through an American operation called Paperclip, scientists were discreetly taken out of Germany en masse and installed in positions at American companies and universities, so that those who had collaborated with the Nazi regime (such as Wernher von Braun, the father of the V2 ballistic missile, member of the NSDAP and the SS) wouldn't fall into the hands of international justice. It was partly thanks to the breakthroughs of these experts in chemical weapons, space exploration, ballistic missiles, and jets that the United States benefited from a technical advantage during the Cold War. Numerous innovations from other sectors were also stolen, including electron microscopes, cosmetics formulas, recording devices, insecticides, and a machine for distributing paper napkins. The United Kingdom also partook of the feast. The historian John Gimble estimates that the Americans and the British made off with German intellectual property worth $10 billion at the time, the equivalent of $100 billion today. The French were much less involved in this siphoning off of German expertise. Unlike the other Allies, they didn't think it was possible to take German technologies out of their context and apply them at home. Nonetheless, the French military and aeronautics sectors brought several hundred scientists to France, particularly those who had worked on the V2 rocket. Newly transplanted German engineers participated in the development of the first fighter jet engines, the first Airbuses, the first French rockets, submarines, torpedoes, radar, and tank engines, allowing France to make important advances in its military capabilities. As for the Soviets, they put thousands of German experts—including Wernher von Braun's assistant—on trains to the Soviet Union with their families, enlisting them without ever asking their permission. These German scientists opened the way, at least indirectly, for the USSR to launch Sputnik, the first man-made satellite, in 1957.

Despite these kinds of conflicts of interest, the Allies at least had the integrity to sanction, sometimes strictly, a number of war criminals and Nazi officials, giving Germans the foundations of a vague understanding of the harm a regime like the Third Reich could enact. Thanks to these efforts, my aunt Ingrid, who was born in 1936, told me that she had known in early adolescence that "the Nazis had committed crimes," because "it was mentioned in school, and even in the media," where she had seen photos of concentration camps. I was astonished, since my father, who was born in 1943, had always described a total amnesia after the war. Then I realized that Ingrid had gone to school at the moment when the Americans in Mannheim had begun trying to "reeducate" the people, but by the time my father was educated, the parenthesis of denazification had already closed.

In 1949, the Western occupiers authorized the fusion of their three zones to found a new Federal Republic of Germany and allowed Germany to benefit from the Marshall Plan, a program that offered loans to most states in Western Europe to help with their reconstruction after the war. My father often says, "Germany was lucky to have been treated with such leniency after the crimes it committed." Without the Cold War, Germany's fortunes might have been very different.

Excerpted from Those Who Forget by Géraldine Schwarz. Copyright © 2020 by Géraldine Schwarz. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.