Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

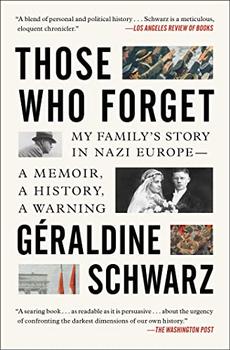

My Family's Story in Nazi Europe – A Memoir, A History, A Warning

by Géraldine SchwarzChapter I

To Be or Not to Be a Nazi

I wasn't particularly destined to take an interest in Nazis. My father's parents were neither on the victims' nor the executioners' side. They didn't distinguish themselves with acts of bravery, but neither did they commit the sin of excess zeal. They were simply Mitläufer, people who "followed the current." Simply, in the sense that their attitude was shared by the majority of the German people, an accumulation of little blindnesses and small acts of cowardice that, when combined, created the necessary conditions for the worst state-orchestrated crimes known to humanity. For many years after the defeat, my grandparents, like most Germans, lacked the hindsight to realize that though the impact of each Mitläufer was tiny on an individual level, it had a cumulative effect, since without their participation, Hitler would not have been able to commit crimes of such magnitude. The Führer himself sensed this and regularly took the measure of his people to see how far he could go, all the while inundating them with Nazi and anti-Semitic propaganda. The first massive deportation of Jews in Germany, which would test the general population's threshold of acceptance, took place in the exact same region where my grandparents lived. In October 1940, more than 6,500 Jews from the southwest of the country were deported to the Gurs camp in the south of France. To accustom their citizens to such a spectacle, German forces of law and order attempted to save face by avoiding violence and commissioning passenger cars—not the freight trains that were later used. But the Nazis wanted to know how much the people would be able to stomach. They didn't hesitate to operate in broad daylight, herding hundreds of Jews through the city center to reach the train station, with their heavy suitcases, their children in tears, and their exhausted elderly—all of this right before the eyes of apathetic citizens who were incapable of exercising their humanity. The next day, the Gauleiter (district chiefs) proudly announced to Berlin that their region was the first in Germany to be judenrein (purified of Jews). The Führer must have rejoiced to be so well understood by his people: the time was ripe for "following."

One episode, unfortunately one of the few, proved that the population had not been as powerless as it hoped to appear after the war. In 1941, protests by citizens and Catholic and Protestant bishops across Germany succeeded in disrupting the planned extermination of physically and mentally disabled people, or those judged as such, that had been ordered by Adolf Hitler in an effort to purge the Aryan race of "life unworthy of life." Although this secret operation, called Aktion T4, was in full swing, having already gassed 70,000 people in specialized centers in Germany and Austria, Hitler relented in the face of public indignation and called off his plan before it could be completed. The Führer understood the risk he would run if the population perceived him as too overtly cruel. This was also one of the reasons the Third Reich expended an insane amount of energy organizing an extremely complex and expensive system to transport Jews from all over Europe to isolated camps in Poland, where they were murdered far from the eyes of their fellow citizens.

But in the aftermath of the war, no one, or almost no one, in Germany asked themselves what might have happened if the majority of citizens had not followed the current, but instead turned against a politics that had revealed relatively early its intention to crush human dignity under its heel. Going along with these politics, like my grandpa, my opa did, was so widespread that this crime was mitigated by its banality, even in the eyes of the Allied forces who got it into their heads to denazify Germany. After their victory, Americans, French, British, and Soviets divided the country and Berlin into four zones of occupation where each engaged in eradicating the Nazi elements of society with the help of German arbitration hearings. They determined four degrees of implication in Nazi crimes, the first three of which theoretically justified the opening of a judicial investigation: the "major offenders" (Hauptschuldige); the "offenders" (Belastete); the "lesser offenders" (Minderbelastete); and the "followers" (Mitläufer). According to the official definition, this last term designated "those who did not participate more than nominally in National Socialism," in particular "the members of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP)… who only went so far as to pay membership fees and attend required meetings."

Excerpted from Those Who Forget by Géraldine Schwarz. Copyright © 2020 by Géraldine Schwarz. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I find that a great part of the information I have was acquired by looking something up and finding something else ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.