Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

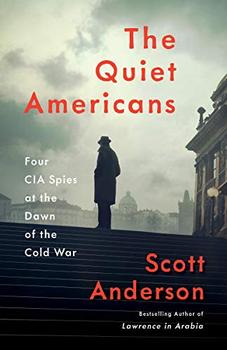

Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War--A Tragedy in Three Acts

by Scott Anderson

It was a call Wisner had been awaiting ever since joining the military three years earlier. In that time, his lot had been to look over legal briefs and shuffle paper, to sit in a back-base office and collate the fieldwork of others. Now, by being dispatched to Istanbul, he was finally going into the field with the opportunity to accomplish something tangible, and he set to the housecleaning mission in Istanbul with a zeal. OSS higher-ups swiftly took note of the contrast between their two men in Turkey; just days after his arrival, Wisner was made head of the Secret Intelligence branch of OSS Istanbul, then shortly after named chief of the entire mission, with Macfarland bundled off to a posting in Yugoslavia where he could do little harm. At long last, Frank Wisner had arrived. The inauspicious trappings of his meeting with Macfarland at the Park Hotel notwithstanding, he was now on his way to becoming one of the most important and powerful figures of the American intelligence community in the twentieth century.

Childhood acquaintances of Frank Gardiner Wisner rarely recalled seeing him walk; he seemed to run everywhere. Even as a boy, he fairly crackled with a kind of impatient energy. In a photograph taken of him around the age of eight or nine and in which he is posing with two other boys, he appears to be practically bursting out of his Sunday suit, as if clothes are just another thing getting in his way, slowing him down.

Wisner was born in the town of Laurel, in the swampy, yellow pinelands of southeastern Mississippi. Even today, Laurel dubs itself "the town that lumber built," although "lumber" might more accurately be traded out for "the Iowans." In the early 1890s, a group of prospectors from eastern Iowa moved into the economically moribund Deep South town, and proceeded to both buy up vast tracts of the surrounding yellow pine forest, and then to build a state-of-the-art lumber mill. Among the newcomers was Frank Wisner's father, Frank George.

Their timing was propitious, for within a few years the lumbering of Southern Yellow Pine was experiencing a nationwide boom, making the Midwestern transplants in Laurel—along with the Wisners, there were the Gardiners and Eastmans—fabulously wealthy. According to one local historian, by the 1920s Laurel boasted more millionaires per capita than any city in the nation, and had converted the once scrubby little town in the pinelands into an unlikely architectural showcase, with a park designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and mansions lining its own Fifth Avenue.

At its heart, Laurel was a boomtown. As such, it had far more in common with, say, the mining settlements of Montana or the oilfields of California than with its Mississippi counterparts. In this most rigidly segregated state of the Deep South, blacks and whites worked alongside each other in Laurel's Eastman-Gardiner lumber mill, and there was a degree of racial intermingling virtually unheard-of elsewhere in Mississippi. In the black sections of town, the Iowans funded parks and streetlights and, in 1926, one of the first high schools for black children in the state, a development regarded as shocking, even subversive, by many Mississippi whites at the time.

All of this made Frank Wisner, born in Laurel in 1909, something of an oddity, a hybrid of two very different cultures. While his childhood bore all the hallmarks of the privileged white Southerner—he was raised by a black nanny, and black housekeepers tended to the expansive Wisner home on Fifth Avenue—his family had little in common with the Mississippi "aristocracy," those wealthy landowning families who traced their roots back to pre–Civil War days and who remained steeped in nostalgic notions of the Old South. Instead, from a very early age, Frank Wisner had his sights set beyond Mississippi. After graduating from the local high school at sixteen, he was dispatched to one of the South's better preparatory boarding schools, Woodberry Forest in Virginia, then sent on the obligatory grand tour of Europe prior to going to college. For his part, Frank Wisner never truly regarded himself as a Southerner except, his middle son, Ellis, recalled, on those occasions when outsiders denigrated the region. "That's when he got his back up," Ellis Wisner recalled. "If people made fun of it, that's when he became a Southerner."

Excerpted from The Quiet Americans by Scott Anderson. Copyright © 2020 by Scott Anderson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

There are two kinds of light - the glow that illuminates, and the glare that obscures.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.