Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

It cannot possibly be true, can it, the story about Toscanini losing patience during a rehearsal with a soprano, grabbing her large breasts and crying, If only these were brains!

Later came "Men don't make passes at girls with fat asses."

I can see them, this man and this woman, at the department dinner that will surely follow the event, and which, because of who he is, will be a fine one, at one of the area's most expensive restaurants, and where it's likely they'll be seated next to each other. And of course the woman will be hoping for some intense conversation-no small talk-maybe even a bit of flirtation, but this will turn out to be not so easy given how his attention keeps straying to the far end of the table, to the grad student who's been assigned as his escort, responsible for shuttling him from place to place, including after tonight's dinner back to his hotel, and who, after just one glass of wine, is responding to his frequent glances with increasingly bold ones of her own.

It looks like it might be true. I googled it. According to some reports, though, he didn't actually grab the soprano's breasts but only pointed at them.

During the obligatory recitation of the speaker's accomplishments, the man lowers his gaze and assumes a grimace of discomfort in an affectation of modesty that I doubt fools anyone.

If grades had depended more on how much I absorbed from lectures than from studying texts I'd have failed out of school. I don't often lose concentration when I'm reading something or listening to a person converse, but talks of any kind have always given me trouble (the worst being authors reading from their own work). My mind starts wandering almost as soon as the speaker gets started. Also, this particular evening I was unusually distracted. I had spent all afternoon in the hospital with my friend. I was wrung out from watching her suffer, and from trying not to let my dismay at her condition get the better of me and become obvious to her. Dealing with illness: I've never been good at that, either.

So my mind wandered. It wandered right from the start. I lost the thread of the talk several times. But it hardly mattered, because the man's talk was based on a long article he had written for a magazine, and I had read the article when it came out. I had read it, and everyone I knew had read it. My friend in the hospital had read it. My guess was, most people in the audience had too. It occurred to me that at least some of them had come because they wanted to ask questions, to hear a discussion of what the man had to say, the substance of which they were already familiar with from the article. But the man had made the unusual decision not to take any questions. There was to be no discussion tonight. This, however, we wouldn't know until after he'd finished speaking.

It was all over, he said. He quoted another writer, translating from the French: Before man, the forest; after him, the desert. Whatever must be done to forestall catastrophe, whatever actions or sacrifices, it was now clear that humankind lacked the will, the collective will, to undertake them. To any intelligent alien, he said, we would appear to be in the grip of a death wish.

It was over, he said again. No more the faith and consolation that had sustained generations and generations, the knowledge that, though our own individual time on earth must end, what we loved and what had meaning for us would go on, the world of which we had been a part would endure-that time had ended, he said. Our world and our civilization would not endure, he said. We must live and die in this new knowledge.

Our world and our civilization would not endure, the man said, because they could not survive the many forces we ourselves had set against it. We, our own worst enemy, had set ourselves up like sitting ducks, not only allowing weapons capable of killing us all many times over to be created but also for them to land in the hands of egomaniacs, nihilists, men without empathy, without conscience. Between our failure to control the spread of WMDs and our failure to keep from power those for whom their use was not only thinkable but perhaps even an irresistible temptation, apocalyptic war was becoming increasingly likely... .

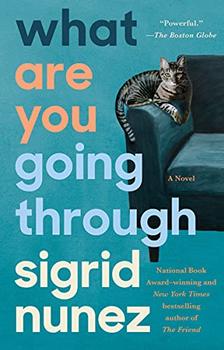

Excerpted from What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez. Copyright © 2020 by Sigrid Nunez. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The longest journey of any person is the journey inward

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.