Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Switzerland

It's been thirty years since I saw Soraya. In that time I tried to find her only once. I think I was afraid of seeing her, afraid of trying to understand her now that I was older and maybe could, which I suppose is the same as saying that I was afraid of myself: of what I might discover beneath my understanding. The years passed and I thought of her less and less. I went to university, then graduate school, got married sooner than I imagined and had two daughters only a year apart. If Soraya came to mind at all, flickering past in a mercurial chain of associations, she would recede again just as quickly.

I met Soraya when I was thirteen, the year that my family spent abroad in Switzerland. "Expect the worst" might have been the family motto, had my father not explicitly instructed us that it was "Trust no one, suspect everyone." We lived on the edge of a cliff, though our house was impressive. We were European Jews, even in America, which is to say that catastrophic things had happened, and might happen again. Our parents fought violently, their marriage forever on the verge of collapse. Financial ruin also loomed; we were warned that the house would soon have to be sold. No money had come in since our father left the family business after years of daily screaming battles with our grandfather. When our father went back to school, I was two, my brother four. Premed courses were followed by medical school at Columbia, then a residency in orthopedic surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery, though what kind of special we didn't know. During those eleven years of training, my father logged countless nights on call in the emergency room, greeting a grisly parade of victims: car crashes, motorcycle accidents, and once the crash of an Avianca airplane headed for Bogotá that nosedived into a hill in Cove Neck. At bottom, he might have clung to the superstitious belief that his nightly confrontations with horror could save his family from it. But on a stormy September afternoon in my father's final year of residency, my grandmother was hit by a speeding van on the corner of First Avenue and Fiftieth Street, causing hemorrhaging in her brain. When my father got to Bellevue Hospital, his mother was lying on a stretcher in the emergency room. She squeezed his hand and slipped into a coma. Six weeks later, she died. Less than a year after her death, my father finished his residency and moved our family to Switzerland, where he began a fellowship in trauma.

That Switzerland—neutral, alpine, orderly—has the best institute for trauma in the world seems paradoxical. The whole country had, back then, the atmosphere of a sanatorium or asylum. Instead of padded walls it had the snow, which muffled and softened everything, until after so many centuries the Swiss just went about instinctively muffling themselves. Or that was the point: a country singularly obsessed with controlled reserve and conformity, with engineering watches, with the promptness of trains, would, it follows, have an advantage in the emergency of a body smashed to pieces. That Switzerland is also a country of many languages is what granted my brother and me unexpected reprieve from the familial gloom. The institute was in Basel, where the language is Schweizerdeutsch, but my mother was of the opinion that we should continue our French. Schweizerdeutsch was only a hairbreadth removed from Deutsch, and we were not allowed to touch anything even remotely Deutsch, the language of our maternal grandmother, whose entire family had been murdered by the Nazis. We were therefore enrolled in the École Internationale in Geneva. My brother lived in the boardinghouse on campus, but as I'd just turned thirteen, I didn't make the cutoff. To save me from the traumas associated with Deutsch, a solution was found for me in the western outskirts of Geneva, and in September 1987 I became a boarder in the home of a substitute English teacher named Mrs. Elderfield. She had hair dyed the color of straw, and the rosy cheeks of someone raised in a damp climate, but she seemed old all the same.

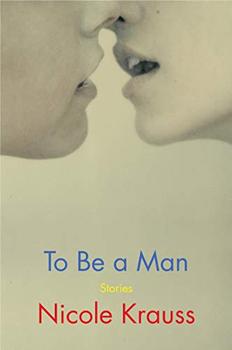

Excerpted from To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss. Copyright © 2020 by Nicole Krauss. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.