Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Clarey spoke in some strange language none of them understood. What little English she did know was poor enough that she couldn't have possibly explained where Pa had gotten her from or if there was a home or a family out there, or anybody she missed. Clarey had the raven hair and dark eyes and high bones of the Indians who'd claimed these mountains before getting chased off to Ohio or married in with white farmers and timbermen. Her strange looks had been Ash's only clue to who, or what, she might be. Pa had just led her in the door one day last spring and said, "This is your new stepma. Name's Clarey. You show her where things are."

The girl had stood there stoop-shouldered and trembling a little, her gaze darting uncertainly toward the twins and Ash, as if she was more than surprised to end up in a two-room house with three half-grown kids in it.

And that was that. Pa had doted on Clarey like a new prize for a while. It'd given Ash the feeling that if things got too crowded and somebody had to go, it'd be Ash and Dab, and maybe Blue, too, though Pa would be more likely to hang on to Blue for work, since he was a boy. Ash might've gone to the woods and figured out how to get by on her own—she could hunt and she could fish and forage—but with Dab and Blue being just seven, and Blue having a foot that'd healed lame after getting caught in the wagon spokes, there wasn't much way.

Things had gone better for a month or two, with a new stepma around. Clarey could cook and she hadn't turned out to be lazy. But then Clarey's thin body had started thickening and rounding. Pa had gone off timbering and left them all there to sort things out on their own. Then the baby had come early and died, and Clarey had taken to the bed.

The last of the buckwheat flour had played out first, and later the cellar goods. All there'd been for a while was whatever Ash and the twins could trap or gather or catch in the streams … and the apples working their way toward ripe, promising better times ahead.

They'd started picking as soon as they could, a harvest crew of four, fighting off the birds and squirrels and the other creatures that would steal the bounty. Black bears had come at night and roared and grunted, bouncing their weight against the cellar doors, while the twins cried and huddled in their bunk. Ash had sat up in the rocking chair, the old rifle propped in her lap, but the long days and fitful nights had proven worthwhile, as had the trouble of hitching the rawboned bay mule and driving him slow and easy down the mountain to find just the right places.

The sorts of places where there were people with money and a taste for apples.

Places where a wagon with three little hill kids and a strange, solemn, dark-eyed girl wouldn't be chased off by people who throw rocks and wave their fists and stab their fingers through the air, pointing away from their houses and storefronts and shade trees.

"Hillbillies! White trash! Go on. Get away!"

It's not that Ash hadn't heard the words before. In the far back of her memories was the time she went off to school one fall, riding double on the mule with the brother who was just a year older. The children there called them names and pulled her hair, but the teacher was kindly.

She said Ash was a very pretty little girl, with her chestnut hair and green eyes. And she said that Ash was smart. The teacher sent home books and fat pencils and pads of paper with big lines to write on. Magazines for Ma, too. And even a sewing pattern one time, neatly traced onto butcher paper, ready for Ma to cut out.

But by early spring, Brother had caught a fever and died, and nothing was the same after. Not with Pa, or with Ma, or with school. The books stayed, though. The teacher never came up the mountain to get those. If Pa wasn't around to yank the books away and tear them up, Ma and Ash leafed through the pages together. That was how Ash learned letters and words and saw pictures of places far away from the mountain, like the factory towns and mills along the Hudson, and the big city where Grandma and Grandpa got off the ship from the Old Country before they came north to the Berkshire foothills.

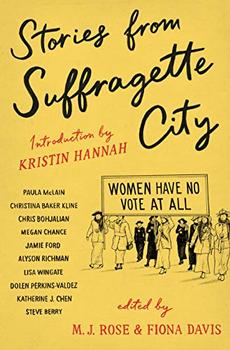

Excerpted from Stories from Suffragette City by M.J. Rose and Fiona Davis. Copyright © 2020 by M.J. Rose and Fiona Davis. Excerpted by permission of Henry Holt and Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Second hand books are wild books...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.