Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

At the top of the hill, the desert stretches below me. There they are. I see hundreds, maybe thousands, of Kochi nomads in reds, greens, blues, and every tone of beige and gray. This is what infinity looks like. An undulating mass of men, women, children, animals, and tents against a wall of sky. I see rifles slung across men's backs, the glint of steely blades at their hips. Fearless, was how my father described them. Fearless and proud.

I have few memories of my mother, Dorothy, but one stabs into me now. I used to run to greet the nomad caravans when they came into town because I wanted to play with the children. My father told me they lived off the land and fought for what was theirs, that even their youngest were brave as lions, and I longed for adventures with six-year-old nomads in the desert. My American mother would stop me, my hand in her iron grip until my fingers hurt as she told me about their thousand-year-old laws, by which even unintentional sins could be capital crimes.

I try to forget her words as I start down the sloping highway. I cross the line where asphalt gives way to sand. It takes me eighteen steps to be noticed and thirty to reach the first goatskin tents. It must have taken the girl less than four running steps from the side of the road to the middle of it. I try to banish the image of that blur. But a child's voice whispers, Look at me, from the deepest recesses of my mind.

Kochis of every age assemble to take in the curious sight of us. For years, they will talk about the stranger who walked among them wearing city clothes and carrying a dead girl. I meet the gaze of an old man, his face a study in shadow, strands of gray escaping from his turban.

"Telaya," the man says, pointing to the girl. Then he asks, "What happened?"

I cannot say, "I found her like this. Someone must have hit her." There is no phantom killer; there is only me. I tell him she was running so fast that I didn't have time to stop. He watches me in silence.

The crowd hovers, a ring of strangers coiling and uncoiling like a cobra. Staring at the corpse, people ask questions I don't answer. Others are quiet. I want them all to disappear. The accident and the girl's death are a private disaster between her and me, made profane by prying eyes and whispered speech.

"Go that way," says the old man.

He points to more tents, more sheep, and more people in bold colors lit brighter by the implacable sun. As I walk, people abandon their tasks to join the silent congregation forming behind me. I pass two men brushing strips of shorn wool. Sitting cross-legged on a rug speckled with sand, girls who would be children in America but are women here sew tea leaves into pouches. As I pass, the sounds of life and work stop, and I feel as if the silence will make me deaf or blind or mute, destroy one of my senses to match the loss of some other indescribable thing the moment the girl died. A few feet away, several tents are wide open. They are brimming with artifacts, jewels, carpets, and mirror-dotted clothes. These are things the nomads will sell as they trek from village to village on their way to Kabul, Ghazni, Jalalabad. But today, I am the wanderer and the nomads are the ones who are still.

A woman sitting on the sand points a bony finger, not looking up from her lap. Two women polishing copper plates notice as I make my way toward them. One of them begins to rise, then sees what is in my arms and falls back to her knees with a stifled cry. Leaning against a younger woman, Telaya's mother sobs, terror and sorrow melding together on her face. I am not a parent, though only a few months ago, I thought I would be. When I see her fear, I think I know. I want to embrace her. I hear myself utter worthless apologies, dwarfed by the enormity of her pain and of what I have done.

"Baseer!" Telaya's mother cries out.

I turn around. The girl's father is only a few feet behind me, staring. His hands start to shake. His eyes widen. "Telaya?" He takes her in his arms, and all I had planned to say is replaced by all I do not. I am a fraud, the quixotic wizard behind the curtain who can't make anything right. I hear Baseer's fractured breath, a whispered word to his dead child. On his face, I see that same fear. Telaya's mother is crying freely now.

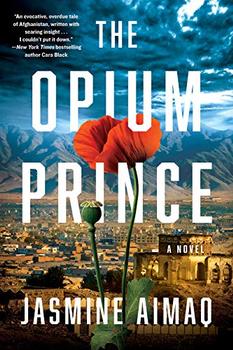

Excerpted from The Opium Prince by Jasmine Aimaq. Copyright © 2020 by Jasmine Aimaq. Excerpted by permission of Soho Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

They say that in the end truth will triumph, but it's a lie.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.