Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Then the crowd ebbs, parting for three tall men with silver beards. Word has spread to the elders, who have left their work, their tea, their wives, and come here to deliberate my crime. I meet their gaze as they approach, hoping Rebecca is still inside the car and will drive off without me if she must.

I hear one of the elders say, "Go find Taj."

There is some commotion as young boys spin this way and that, nodding and shouting, "Where's Taj Maleki? Get Taj!"

A man with thick sideburns cuts through the now-silent crowd. He reaches me and stops. One finger gleams with gold, an onyx adorns the front of his turban, and his piran tomban tunic and trousers are finer than the other men's, made of silk. A revolver sits in his holster, a Colt with a delicate pattern engraved on its grip. I stand before this strange man whose eyes are bereft of light, as if even the sun conceded defeat long ago.

"Who are you?" Taj asks in Farsi. I am relieved I speak the language, and that no one here could guess that I spoke more English than Farsi as a child.

"Daniel Abdullah Sajadi."

The man takes a step forward, but his face betrays nothing. The Kochis will not recognize the name Sajadi like people in the city do. Maybe this man knows who I am, maybe not. He watches me silently.

"Did you not see her?" His voice is as flat as his gaze.

"She ran straight into the road."

"And now she is dead."

"I'm sorry."

Taj nods. "Who do you work for?" he says. From his dialect, I hear that he isn't a Kochi. He's from the city.

"The American government."

A thousand eyes are on me. The only two people not looking at me are Telaya's parents, who are standing behind Taj. It seems indecent to watch a mother and father in their grief. I stare instead at the horizon. An outsider would not know that this arid land is a great fraud of nature. Just behind these deserts are acres of vibrant opium poppies with emeraldgreen leaves, thriving under the sun. The great Yassaman field, with its rich bounty of flowers, is not far. Nature has surrounded these fields with the most fallow land on earth, giving the poppies better camouflage than it has given me. It is these flowers that I have dreamed of killing since I was a boy, not the children who help harvest them, the descendants of those who followed my father into war against the British empire.

These thoughts speed through my head, but her voice slices through all of them. Look at me, says the dead girl. The desert has flung me at the feet of its dwellers. I am that most vulnerable of creatures: a man out of context.

I can almost smell the poppies on the wind. They seem so trivial now, when just hours ago, they weighed more than anything else in my life. I fought for months at the office to convince my colleagues to begin the Reform with Fever Valley's largest field.

Taj looks at Telaya's corpse. Paper-white bone protrudes from her arm. Something glimmers in the sun: a shard of glass, lodged above her eyebrow, nearly invisible in the curve of her hair. I feel a throbbing pain above my own eye.

Baseer sobs, his words tumbling over each other in despair. "God, why have you done this to us? I have no other daughters." His wife squeezes his hand.

"He killed her," Baseer says to Taj, pointing at me as if sentencing me to join his daughter in death. Between cries, he whispers, "She was the only thing of value in my life."

The crowd is still silent, watching them. Taj places a hand on Baseer's shoulder and says, "What a terrible day for you."

His words are compassionate, but I wonder if the others can tell that the man is not. He is probably one of the callous merchants from the city who trick nomads into parting with their wares for less than they are worth, who travel with them for days at a time, choosing the best rugs and jewels and bartering them for a little food, money, perhaps medicine. Kochis are sophisticated tradesmen, too sharp to fall for such tricks, and yet there are exceptions. Some earn enough to become members of the country's sliver of a middle class, but Taj Maleki must be one of the tricksters taking advantage of those who do not with his expensive clothes and his cheap sympathy.

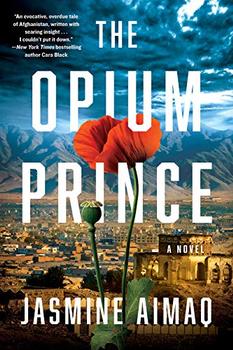

Excerpted from The Opium Prince by Jasmine Aimaq. Copyright © 2020 by Jasmine Aimaq. Excerpted by permission of Soho Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

It was one of the worst speeches I ever heard ... when a simple apology was all that was required.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.