Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

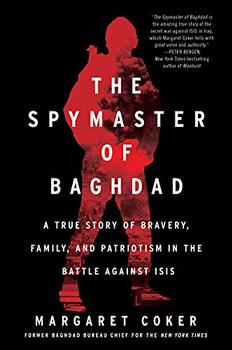

A True Story of Bravery, Family, and Patriotism in the Battle against ISIS

by Margaret Coker

Later, over tea with Harith, as the city still celebrated, Munaf told his brother his secret wish. He wanted to help bring justice to Iraq, serve the people trampled by Saddam's brutality. He wanted to be a policeman.

Under Saddam's twenty-five-year rule, Iraqis had come to refer to their nation as the Republic of Fear due to the web of police agencies that had the sole purpose of protecting the regime instead of defending the citizenry against its abuses. Shiites were excluded from almost all jobs in the security forces because the Sunni regime believed they were a national security threat. No one in the al-Sudani family, or their social circles, had ever dreamed of being an officer. Some uncles and cousins had been drafted to fight on the front lines during the Iran-Iraq War, but they had been mere foot soldiers, cannon fodder, not leaders.

Even on a day full of hope, Munaf's dream was fantastical. No one in the ever-growing family could spare an ounce of care or effort for the desires of the third-born son. For his entire life, Munaf had been a pale afterthought in their father's fixation on bringing glory and prosperity to the al-Sudanis. For proof, he had only to look at the collection of photos hanging on the beige-colored walls of the room where the family gathered each day for meals. The largest portrait was of Abu Harith and his wife dressed in stylish Western clothes. Um Harith had a warm smile, her peaches-and-cream complexion glowing and her bouffant bob as stiff as starch as she held a light-haired toddler with curls and wide brown eyes—young Harith, gazing slightly beyond the photographer, as if looking to the future. Next to that photo, in an elaborate gold frame, was another portrait of Abu Harith, holding his somber firstborn as an infant. A third photo showed Mrs. al-Sudani with a leopard-spotted headscarf tied loosely over her dark brown hair while holding Harith with one hand and another infant, her second son, Muthana, on her lap. Other family memories immortalized on the wall included a picture of Um Harith's mother and aunt. Taken shortly before they died, the two women with prim expressions were sitting on a hard, wooden-backed sofa, their bodies cloaked in the severe black chador worn by pious Shiites.

Absent from the wall was any sign of Munaf, or the children born after him. Some nights, as the al-Sudanis ate under the gaze of the photographs, Munaf wished he could have squeezed onto that hard sofa at his grandmother's house when the photographer was preparing his shot. He hated being overlooked, but he slowly learned to exploit the advantages that his invisibility had presented to him. While Abu Harith ordered his eldest son to work with him each day in his shop, Munaf had the freedom to play soccer after school. He could skip chores and bring home mediocre grades knowing that if Abu Harith noticed, his scolding would be light, his disappointment fleeting.

And why should he excel at school? Why should he exert himself? He wasn't being raised in a meritocracy. The hierarchy of the family was a natural order reinforced by almost every interaction. On Friday afternoons Abu Harith would host his brothers for lunch after the weekly noon prayers. The men would sit around the cream-tiled floors of the family room, smoking and sipping tea. Younger children flitted in and out, serving fruit and nuts and clearing teacups, eavesdropping on the conversations about poetry and sports. Harith was a frequent topic of discussion as well, not Munaf. Their father would boast to the gathered relatives how Harith would be the first in their family to get a university degree and a prestigious job, and bring honor to the al-Sudanis.

Munaf never begrudged Harith the attention bestowed by their father. In fact, Munaf and his brothers often pitied the eldest. Once Harith was kicked out of university, Munaf could see how painful the humiliation was for his brother. There weren't many professions in Saddam City to choose from. Lower-ranking civil service jobs like teaching or nursing might be possible, but it was simply assumed that most young men would apprentice with their father or uncles. Either that, or they would join the growing ranks of the unemployed. In the al-Sudani family, Harith's ten siblings understood that Harith was expected to do something respectable, like become an engineer. The second son was expected to join their father in his small graphic design business. When it came to Munaf, there was no plan at all.

Excerpted from The Spymaster of Baghdad by Margaret Coker. Copyright © 2021 by Margaret Coker. Excerpted by permission of Dey Street Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

In youth we run into difficulties. In old age difficulties run into us

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.