Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

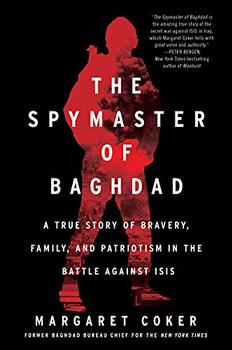

A True Story of Bravery, Family, and Patriotism in the Battle against ISIS

by Margaret Coker

Even so, the al-Sudani family lived a relatively comfortable life, at least by the standards of their slum, and Munaf and his brothers saw their corner of Saddam City as a small piece of paradise. Abu Harith and his cousins had built the family's three-room unpainted cinder block home on a corner lot amid a warren of hard-packed dirt lanes where the extended family all lived and where children could play unsupervised at all hours. City sanitation workers never ventured into their neighborhood, but instead of cursing the government neglect, Abu Harith viewed the situation as a blessing. The family's goats munched on mounds of rubbish instead of feed that he didn't have the money to buy. Mothers recycled glass jars and bottles out of simple necessity. Siblings wore each other's hand-me-downs. Neighbors knew each other's names and each other's business.

But in 1999, the whole nation was suffering. Saddam's political feud with the Americans had brought Iraqis nothing but pain. Iraq was suffocating under international economic sanctions: children were dying from preventable diseases for a lack of medicine; the oil industry was rusting because there were no spare parts for machinery and infrastructure; and the once proud nation that boasted the birthplace of human civilization was on its knees.

In the absence of any political debate, Iraqis turned toward religion, and a revered Shiite leader, Ayatollah Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr, became a beacon for the opposition, using his sermons to give voice to the belief of Iraqis from all faiths: Saddam Hussein was the reason for their suffering. Saddam had to go.

The ayatollah had been banned from television, so his representatives traveled around Iraq preaching directly to the faithful in mosques and spreading his message by word of mouth. Even Iraqis like the al-Sudanis, who steered clear of politics, understood the bravery it took to speak such things aloud.

The nation's impotent rage exploded in late February of that year, when state news agencies announced the death of Ayatollah al-Sadr and two of his sons. The terse statement gave no details, only stating that the men had already been buried before sundown, per Islamic rites.

Bewildered Shiites from the southern port city of Basra to Saddam City rushed to their mosques to pray for their spiritual leader's soul. Rumors spread through the crowds like an infection. Several months earlier, two of the ayatollah's closest aides had been assassinated. Three weeks before his own death, the ayatollah had been ordered by a government official to tone down his criticism. Even though they had not seen the body or known any details, the surging crowds were convinced that their leader had been killed by the regime.

In Saddam City, emotions were raw. Hundreds of men who had gathered for days at the Imam Hussein Mosque to pray for Ayatollah al-Sadr whipped themselves into a frenzy. A battle cry rang out through the mosque and into the streets. Death to Saddam, death to Saddam. The call brought hundreds more men out to the crumbling sidewalks and potholed streets, building to a crowd that became the largest popular demonstration since 1991, when the Americans launched the first Gulf War and called on Iraqis to topple the dictator themselves.

The al-Sudani boys didn't understand that trouble was brewing. It was a matter of luck that all the boys got home before the bullets started to fly.

Harith and his friend Ali had taken a bus that morning into Baghdad. Ali was just about to turn eighteen, and like all Iraqis, they had to register for mandatory army service at that age. However, both were finishing up their high school exams, hoping to put off their duty by winning a slot to study at university.

Ali wanted company as he navigated the bureaucracy of the military recruiter's office. Harith, with his deft use of words and manners with adults, was whom he asked. By late morning, the two friends were heading back to Saddam City on a city bus when they noticed from the bus window that truckloads of soldiers wearing helmets and carrying anti-riot gear were lining the main street leading into their district. Behind them on the four-lane road, large trucks carrying tanks and armored vehicles were clogging the main artery.

Excerpted from The Spymaster of Baghdad by Margaret Coker. Copyright © 2021 by Margaret Coker. Excerpted by permission of Dey Street Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.