Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

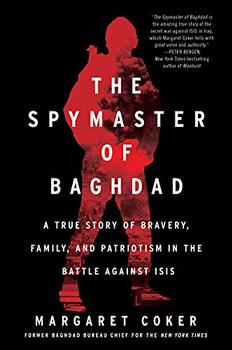

A True Story of Bravery, Family, and Patriotism in the Battle against ISIS

by Margaret Coker

Each Friday in the al-Sudani family majlis, the room in every Iraqi house reserved for guests, men would sit on the floor cushions spread across the room, sip tea, and listen to Abu Harith recite poems that he had memorized as a boy or read in the newspapers that week. Harith enjoyed these afternoons more than anything else in his week, enchanted by the rhythms of a couplet and the allegorical weave of sonnets. He'd dissect these readings like a mathematician, finding beauty in the form and meter as much as in the emotions the poems could elicit.

When he reached the sixth grade, Harith also found a way to profit from his hobby.

The all-boys middle school, Al Joulani, was a ten-minute walk from the al-Sudani home in Saddam City. It was housed in a nondescript low-slung concrete stucco building, one of thousands built under the central government's education drive in the 1970s and 1980s. Like most of the district's buildings, the school appeared old from the moment it was first opened. Baghdad's intense summer sunshine had bleached the canary yellow walls the color of egg yolk. Patched plaster in the hallways couldn't completely hide cracks along the ceiling joints caused by the humidity. In Harith's neighborhood, these flaws didn't matter much anyway. No school inspector would be coming to check the work of the contractors. The residents themselves weren't going to take it up with the authorities. Nothing good would come of someone raising a complaint, exposing themselves as potential troublemakers to those in power.

Saddam City's reputation made recruiting teachers difficult. So no one questioned why the boys at Al Joulani had an empty hour in their school day, unchaperoned except for the obligatory portrait of Saddam Hussein peering down at them with his thick mustache and dead eyes. Without adult supervision, most of the boys went wild. Some organized wrestling matches. Others played games with string and spitballs. Many sat in groups discussing girls, who they might fall in love with, who might let them steal a kiss, and who might let them go further than that.

Harith, however, spent the hour alone at the narrow wooden desk that he normally shared with two other boys. At thirteen, Harith had established himself as the smartest boy in the class, a status attributable less to his natural cleverness and more to his father's discipline over homework. He was also good at writing poetry.

Abu Harith's control over Harith extended into all parts of life, dictating everything from what color pants he could wear—only brown and never black—to how many hours the boy could sleep. It was lucky for Harith that his father also considered poetry one of the foundations of a respectable education.

Harith sold the poems he wrote at school to classmates wanting to impress their sister's friend or a neighbor's daughter. Soon, word spread around the neighborhood that Harith's work attracted girls like bees to flowers, and his reputation was made. But for all the success of his friends' romances, Harith himself never had any luck wooing a girl. Ali and Wissam used to joke that the djinns from the abandoned house had cursed him when he was inside. Some days, Harith thought they might be right.

By the time Harith turned fifteen, he had no more time for sonnets. It was the mid-1990s and his father's small printing business—where Harith worked both before and after school—had gone bankrupt. After the disastrous war with the Americans, international sanctions tore apart the Iraqi economy. Meanwhile, the al-Sudani family had multiplied and someone had to help Abu Harith feed all ten of his children. So he arranged for his oldest son to work alongside his cousin at one of Baghdad's open-air wholesale markets.

Six days a week, the two young men would rise before dawn. Harith would put on one of his two pairs of brown pants, bought, like all the al-Sudani children's clothes, at the secondhand markets in Baghdad al-Jdeideh, a neighborhood south of Saddam City. He would button up the shirt that his mother had ironed for him the night before, take a piece of bread and white cheese for his breakfast, and eat it while he walked three miles to the Jamila market. For six hours, Harith and his cousin would haul seventy-five-pound bags of rice, flour, and sugar between delivery trucks and market stalls. Harith, who was short and stocky like his uncle, complained that his muscles felt like a tightly wound oud string ready to snap.

Excerpted from The Spymaster of Baghdad by Margaret Coker. Copyright © 2021 by Margaret Coker. Excerpted by permission of Dey Street Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

To make a library it takes two volumes and a fire. Two volumes and a fire, and interest. The interest alone will ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.