Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

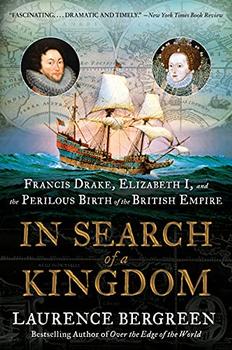

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence BergreenBook I

The Pirate

Chapter I

The Island and the Empire

On the morning of December 13, 1577, Francis Drake, a pirate and former slaver, ordered his small fleet in Plymouth, England, to weigh anchor. The ships stood out against a bleak background. They were colorfully painted, with billowing sails, and boisterous sailors calling to one another.

Plymouth lies 190 miles southwest of London, surrounded by two ancient rivers, the Plym and the Tamar, both running into Plymouth Sound to form a boundary with the neighboring county, Cornwall. It was a tranquil town, mostly farmland gathering into a peninsula jutting into a bay. Drake, from nearby Devon, made Plymouth his base of operations. The port was recognized for its shipping, and it also served as a hub of the English slave trade. It was not an innocent place. In folklore, Devon harbored witches and the Devil himself.

The fleet's destination was unknown, but they would not be home by Christmas or even the next, not if Drake's ambitious plan was successful. Many aboard had a financial stake in the voyage, and they might return prosperous. Or, just as likely, they might never see Plymouth again. Weeks earlier, the Great Comet of 1577 had passed overhead, an event taken across Europe as a sign, portent, or warning that a great event would soon unfold. Comets, those mysterious, phosphorescent messengers from the far reaches of space, coincided with the commencement of a new age.

Two of the most consequential figures of this era, Francis Drake and Queen Elizabeth, knew the expedition's true purpose: to circumnavigate the globe. If successful, Drake would take his place in history as the first captain to command his fleet around the world—and return alive. For Elizabeth, the expedition was a challenge to the global order, which ranked Spain dominant and England a second-rate island kingdom. Both dreamed the voyage would reap riches. But for the moment, Drake and Elizabeth kept their ambitions to themselves, concealing their plans for the expedition in documents.

Drake allowed the crew to think they were going to raid the coast of Panama for gold, or perhaps set a course for Alexandria, Egypt, in search of currants. These were lucrative but not exciting pursuits. Had the crew known Drake's real intentions, they may well have deserted at the first opportunity. "The Straits were counted so terrible in those days that the very thought of attempting it were accounted dreadful," said a commentator, referring to the treacherous passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, only the most obvious of many obstacles to a circumnavigation attempt. Maintaining secrecy was essential, especially from the men expected to perform the task.

The syndicate backing his voyage had authorized Drake's fleet to cross the Atlantic, navigate the southern tip of South America, explore the west coast of that continent, and prospect for gold and silver—specifically, gold and silver stolen from the Spanish, along with anything else of value aboard Spanish ships that could be carried away. His unspoken commission was to drive out the Spanish from those mineral-rich regions. Nothing was said about a circumnavigation; it was up to Drake to take the initiative as they embarked on a journey that would transform England.

If Francis Drake ever had a moment of self-doubt, he left no record of it. He respected the violence of storms, but they held no terror for him. Drake was thoroughly at ease aboard whatever ship he happened to be sailing, from a pinnace to a flagship. He was just as authoritative and quick-witted on land as he was at sea. As a loyal Englishman, he naturally respected the queen and her court, most of them wellborn and with little use for him, but he was not awed by them. Deference did not come naturally to Drake.

Ultimately, he respected only one force in this world, and that was the Supreme Being. His father, Edmund, had come to preaching late in life, and from him Drake inherited a reliance on absolutes concerning faith. When a sailor signed on to a voyage with Drake, it was understood that he would sing psalms and recite prayers as often as possible, even several times a day. Drake ordered his crew to sing psalms before battles, to give thanks for victories, and, when necessary, to give the dead a Christian burial—and that meant a Protestant burial. Roman rites infuriated Drake, even though the two were at the time far more similar than they are now. Although rough around the edges compared with the upper echelons of the nobility, he yielded to no one in his belief in queen and country, and his disdain for her enemies, especially Spain. His was a simple moral compass, but it was durable and allowed him to negotiate the perilous straits he encountered, both real and imagined.

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.