Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

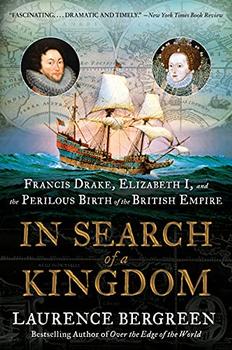

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence Bergreen

Although Drake was the captain, he did not belong to that exalted social rank. But he was unquestionably Protestant and loyal to the queen, and his years of experience in the company of Hawkins, as well as his own daring exploits, testified to his courage, resourcefulness, and skill as a mariner. And the ships arrayed before him would make his ambitions attainable.

Their provisioning was, by the standards of the time, ample: biscuit, powdered and pickled beef, pickled pork, dried codfish, vinegar, oil, honey dried peas, butter, cheese, oatmeal, salt, spices, mustard, and raisins. (Nearly all these items were provided by Drake's longtime Irish supplier, James Sydae.) Scurvy—the loss of collagen, one of the body's building blocks—devastated sailors, and not until 1912 would it become widely understood that ascorbic acid, or vitamin C, available in citrus, vegetables, and beer, prevented it, yet even at this early date, English captains including Drake relied on oranges and lemons as a remedy without understanding why they worked.

English sailors were known for drinking quantities of ale and wine, but the record is silent concerning the expedition's supply of alcohol. More is known about the objects Drake brought along for trading, including knives and daggers, pins, needles, saddles, bridles, bits, paper, colored ribbons, looking glasses, cards and dice, and linens. Carpenters packed staples such as rosin, pitch and tar, twine, needles, hooks, and plates, together with pikes, crossbows, muskets, powder, and shot. Drake himself was fond of luxury items, including perfume (a necessity in an age of negligible hygiene) and dishes made of silver with gilded borders, embossed with his coat of arms.

For navigation, Drake relied on a Portuguese map of the globe as well as a detailed chart of the Strait of Magellan. He carried a copy of the famous account kept by Ferdinand Magellan's chief chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta, The First Voyage Around the World, and consulted it as a guide for both navigation and the management of mutinous sailors. The young Venetian had traveled with Magellan, been at the right hand of the captain general at that fateful hour in Mactan harbor, and was fortunate to be among the handful of survivors of the voyage. His account made it clear that everything—even survival—came with difficulty for Magellan, who perished in the Philippines. It stood as a reminder that attempting to cross the Atlantic, let alone sail all the way around the world—ever changing, poorly understood, and immense—was more than dangerous, it was fated to end in disaster and oblivion. Those drawn to it were likely to be reckless, fearless, and rapacious. They had little to lose and perhaps fame to gain.

Books about the New World were a new and expanding genre at the moment, and Drake brought several state-of-the-art volumes with him, including L'Art de naviguer, published at intervals between 1554 and 1573. This work was a French translation of Pedro de Medina's authoritative Arte de navegar, originally published in eight volumes in Valladolid, Spain, in 1545, and dedicated to the future king of Spain, Philip II. Then there was Martín Cortés de Albacar's Breve compendia, published in Seville and translated into English in 1561. Profusely illustrated, this was the basic text for many captains and covered technical matters such as magnetic declination (the angle between magnetic north and true north) and the celestial poles, hypothetical points in the sky where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects the celestial sphere, a projection of the sky onto a hemisphere. These measurements were useful for a ship to fix her position when out of sight of land. Cortés also discussed the nocturnal, an instrument that allowed a navigator to determine the relative positions of stars in the night sky and to calculate tides, critical for ships in determining when to enter ports. Drake's nautical library included two other standard references: A Regiment for the Sea by William Bourne (1574), which was a translation of Cortés's popular work, and Cosmographical Glasse by William Cunningham, a physician and astrologer (1559).

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.