Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

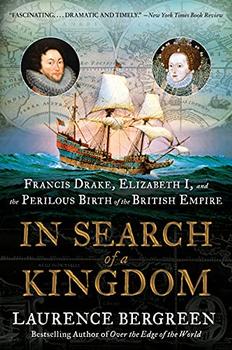

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence Bergreen

Other crew members included a naturalist named Lawrence Eliot; a botanist; several merchants, among them John Saracold, a member of the Worshipful Company of Drapers, a powerful trade association whose origins went back to 1180.

Then there was Francis Fletcher, a priest in the Church of England, tasked with religious observance. Records indicate that he studied at Pembroke College, Cambridge, but did not graduate, and for a brief time he served as rector of St. Mary Magdalen parish in London. Few crew members were literate, so it fell to Fletcher to function as a chronicler. He maintained a detailed narrative of the voyage that would later be gathered and published under the title The World Encompassed. He was an engaging eyewitness, sensitive to the moods of the crew, capable of eloquent descriptions, and appeared to be wholly loyal. Drake followed the example of other captains by taking his personal retainer, Diego, an African who had escaped Spanish enslavement, with him. He was probably the only black member of the crew. They had met in 1572, when Drake attacked the Spanish port of Nombre de Dios in Panama. Because he spoke both Spanish and English, he was particularly useful to Drake and became not merely his servant but also his employee, receiving wages like the other hired hands. And there were relatives, including Drake's younger brother Thomas; his cousin John, only fifteen years old; and a nephew of Drake's cousin and mentor, John Hawkins, who had introduced Drake to the sordid, treacherous, and lucrative slave trade.

With the exception of Thomas Doughty, who signed a will on September 11, 1577, shortly before they departed, and Drake himself, none of the personnel sensed that they were about to commence the most ambitious voyage in English naval history. And even Drake was not sure where he would end up. He would be guided by his hunger for gold and status.

All the while, Spanish spies watched and worried. Their concerns regarding England and especially Drake intensified week by week. On September 20, 1577, Antonio de Guarás, a Spanish ambassador to Queen Elizabeth's court, warned, "As they carry on their evil plans with great calculation, there is a suspicion that Drake the pirate is to go to Scotland with some little vessels and enter into a convenient port, for the purpose of getting possession of the prince of Scotland for a large sum of money; whereupon he will bring him hither convoyed by the Queen's ships that are there."

Drake's calm demeanor gave nothing away. Perhaps he was embarking on another escapade and would go wherever the winds of fate took him—across the entire length of the Mediterranean to the commercial port of Alexandria, Egypt, or along the coast of Africa, or across the Atlantic. As Francis Pretty, Drake's gentleman-at-arms, or military guard, noted: "The 15th day of November, in the year of our Lord 1577, Master Francis Drake, with a fleet of five ships and barques, and to the number of 164 men, gentlemen and sailors, departed from Plymouth, giving out his pretended voyage for Alexandria." Just then the first of many unexpected occurrences altered their plans. "The wind falling contrary, he was forced the next morning to put into Falmouth Haven, in Cornwall, where such and so terrible a tempest took us, as few men have seen the like, and was indeed so vehement that all our ships were like to have gone to wrack. But it pleased God to preserve us from that extremity and to afflict us only for that present with these two particulars: the mast of our Admiral, which was the Pelican, was cut overboard for the safeguard of the ship, and the Marigold was driven ashore, and somewhat bruised. For the repairing of which damages we returned again to Plymouth."

Drake spent weeks restoring the damaged vessel, until "we set forth the second time from Plymouth and set sail the 13th day of December following." The days were short, the air cold and damp, in contrast to the expected warmth of the Alexandrian sun, if Egypt was their destination. Unlike his inspiration, Magellan, who called his fleet the Armada de Moluccas to proclaim his objective, Drake never named his fleet, and kept his options open. They might be headed toward Alexandria; then again, they might not. Another possibility, which promised to be both quick and lucrative, concerned Brazil. If he could reach the coast, avoid vicious Spanish soldiers, and return with quantities of silver and gold, the queen would likely consider his voyage a success. Drake had no intention of dying on a distant beach, as Magellan had, with his body dismembered and his memory disgraced.

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.