Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

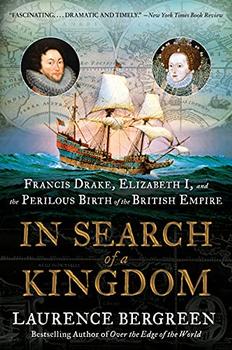

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence Bergreen

Much of Drake's knowledge of South America derived from the controversial records compiled by the Florentine navigator Amerigo Vespucci, who had died in 1512. Vespucci claimed he had made as many as four voyages to the land he called "The New World," and put his name to several influential letters about his adventures (the authorship of the first and fourth letters is contested)—accounts that popularized his discoveries across western Europe. A skillful propagandist, Vespucci composed a vivid portrait of the enormous land known as Brazil, after the pau brasil, the flowering tree growing there in abundance at the time. He told of naked locals rushing to the water's edge to greet (fully clothed) European arrivals. He described how communication was tentative at first, largely in sign language, helped along by the exchange of gifts as proof of peaceful intentions. The Brazilians were "very great swimmers, with as much confidence as if they had for a long time been acquainted with us." The ability made an impression because many Europeans, even sailors, simply could not swim. The women were even more capable in the water than the men: "we have many times found and seen them swimming two leagues out at sea without anything to rest upon." They had ample weapons, "such as fire-hardened spears, and also clubs with knobs, beautifully carved," and they did battle "against people not of their own language, very cruelly, without granting life to any one, except (to reserve him) for greater suffering. When they go to war, they take their women with them, not that these may fight, but because they carry behind them their worldly goods, for a woman carries on her back for thirty or forty leagues a load which no man could bear."

Vespucci cautioned his readers not to underestimate the native peoples of the New World simply because "in their conversation they appear simple." In reality, "they are very cunning and acute in that which concerns them: they speak little and in a low tone: they use the same articulations as we, since they form their utterances either with the palate, or with the teeth, or on the lips." They were highly verbal, the idioms constantly shifting. "For every 100 leagues we found a change of language, so that they are not intelligible each to the other."

At least one of their innovations captivated him: "They sleep in certain very large nettings made of cotton, suspended in the air: and although this fashion of sleeping may seem uncomfortable, I say that it is sweet to sleep in those (nettings): and we slept better in them than in the counterpanes." The hammock, a rope mesh suspended by cords at the ends, was ubiquitous, and caught on with the Europeans, who adapted them to their ships. One sturdy hut, covered with palm leaves, sheltered as many as "600 souls." A village with only thirteen huts contained several thousand souls.

Their concepts of value and property also varied greatly. "The wealth that we enjoy in this our Europe and elsewhere, such as gold, jewels, pearls, and other riches, they hold as nothing; and although they have them in their own lands, they do not labour to obtain them, nor do they value them." Instead, they prized "bird's plumes of many colours," and "rosaries" made of fish bones. They embedded "white or green stones" in their cheeks, lips, and ears. And they were generous, "for it is rarely they deny you anything: and on the other hand, liberal in asking, when they show themselves your friends."

One of their customs was beyond the pale. "They eat all their enemies whom they kill or capture, females as well as males with so much savagery, that (merely) to relate it appears a horrible thing: how much more so to see it, as, infinite times and in many places."

Vespucci was, at the same time, a slaver. He boasted that his ships returned on October 15, 1498, carrying 222 slaves to Cádiz, Spain, "where we were well-received and sold our slaves."

Vespucci's reputation would have faded were it not for a quirk of fate. The New World might have been called "Columbia," after the most celebrated and notorious explorer of the continent, even though he thought he was approaching India. But, in 1507, a year after Christopher Columbus died, a German cartographer, Martin Waldseemüller, produced an enormous world map naming the newly discovered continent "America" after the feminine Latin version of Vespucci's first name, Amerigo. Protests were raised on Columbus's behalf, but Waldseemüller insisted, "I do not see why anyone should justifiably forbid it to be called ... America, from its discoverer Americus [Vespucci], a man of perceptive character; since both Europa and Asia have received their names from women." The name stuck.

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

There are two kinds of light - the glow that illuminates, and the glare that obscures.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.