Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

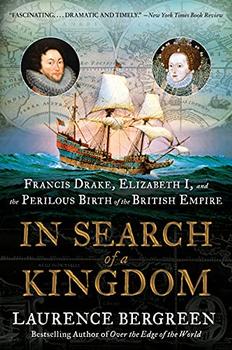

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence Bergreen

Drake's early efforts to wage undeclared war against King Philip II of Spain eventually came to the attention of Elizabeth. Reluctant to antagonize the formidable Spanish empire, which might weaken her position abroad and at home among English Catholics, she came to rely on pirates such as Drake, who were out for themselves as much as they acted on behalf of the Crown.

"Drake!" Her Majesty exclaimed, "I would gladly be revenged on the King of Spain for divers injuries that I have received." This was much easier said than done. Spain was unquestionably the most powerful nation in Europe, its influence augmented by the Catholic Church. England, on the other hand, was a Protestant—actually a semi-Protestant—upstart, isolated and second-rate compared to Spain's preeminence. It was Spain, not England, who ruled the waves. Challenging Spanish dominance required a carefully considered strategy combined with a devil-may-care attitude and fearlessness. It required a captain who thrived on confrontation rather than shrank from it. Drake met and exceeded those requirements. For him, faith and loyalty were matters of life and death. His instincts included a zeal for revenge against Spain and an inordinate fondness for gold.

Emboldened, Drake developed a plan to attack Spanish interests on the Pacific coast of Panama, "by way of the Straits of Magellan." Elizabeth put a thousand crowns behind it. Secrecy was essential. "Her Majesty did swear by her crown that if any within her realm did give the king of Spain to understand," Drake recalled, "they should lose their heads."

Spain had the advantage of size and wealth, but England had Francis Drake. Of all English navigators, only Drake possessed the raw courage and skill to deliver the global influence Elizabeth and her advisers sought. He was never satisfied, always striving for more, as expressed in the opening stanza of a prayer he once wrote: "Disturb us, Lord, when we are too well pleased with ourselves, when our dreams have come true because we have dreamed too little, when we arrive safely because we sailed too close to the shore." No one would ever accuse Drake of hugging the shore; he preferred to be far out at sea, on a broad reach, riding the wind where it would take him, or fighting it when circumstances demanded.

Elizabeth's realm was poor and isolated by comparison with the great Spanish empire, more Beowulf than Camelot. It seemed likely that Spain, led by the methodical Philip II, would soon invade England and replace the Protestant queen, who had already been excommunicated by the pope, with a suitable Catholic monarch, bringing the country into the Vatican fold. The country was half-Catholic, and many of the populace would welcome the development. But Elizabeth's improvised strategy and Drake's daring defied this likely outcome and set England, Europe, and eventually much of the world on a different course. It marked the moment when England, overshadowed by Spain and Portugal, shook off Catholic authority. Drake became the catalyst in England's great transition from an island nation to the British Empire.

All that Drake accomplished on his voyages, especially acts of piracy and violence, he did on Elizabeth's behalf and, as a result of her largesse, for himself. Piracy offered his surest route to wealth and status, and, as the eldest son of a clergyman, he was unlikely to attain these prizes any other way. Elizabeth's reputation in England was never higher than in the years surrounding Drake's voyages. And he might have fancied becoming her beloved, joining the lengthy list of men whose affections she had ensnared. The farther he sailed around the world, the deeper he would sail into her heart, or so he hoped. It would be a long and unlikely journey.

Francis Drake, born in Devonshire in 1541, was the son of Edmund Drake (1518–1585), a farmer turned minister to the faithful at the Royal Dockyard in nearby Chatham, and his wife, Mary Mylwaye. The Drake name resonated across Devon, and his father beseeched a member of the nobility, Francis Russell, to sponsor the infant's baptism, to little avail. Francis Drake spent his youth in obscurity, perhaps because his father became embroiled in religious controversy. William Camden, a British historian and contemporary of Drake, explained, "Whilest he was yet a child, his father embracing the Protestant Doctrine was called into question by the Law of the Six articles, made by King Henry the Eighth against the Protestants, fled his country, and withdrew himself into Kent. After the death of King Henry he got a place among the sea-men of the King's Navy, to read prayers to them: and soon after he was ordained Deacon and made Vicar"—that is, a parish priest—"of the Church of Upnore."

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Great political questions stir the deepest nature of one-half the nation, but they pass far above and over the ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.