Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

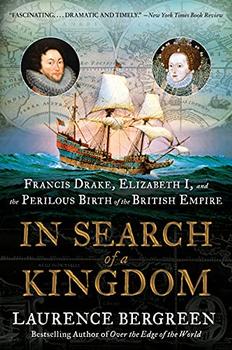

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence Bergreen

Drake's father was too poor to keep his son at home, a circumstance that made all the difference in Francis's life. "By reason of his poverty, he put his son to the Master of a Bark"—a ship with at least three masts—"his neighbour, who held him hard to his business in the Bark, with he used to coast along the shore, and sometimes to carry merchandise into Zeland [Denmark] and France. The youth ... so pleased the old man by his industry, that being a bachelor, at his death he bequeathed the bark unto him by will and testament."

In need of money, young Francis began his career as a slaver under the command of his cousin John Hawkins, who was prominent in the booming English slave-trading enterprise. In 1562 they sailed from Plymouth with three ships and kidnapped four hundred Africans in Guinea, selling their captives in the West Indies. Many prisoners died en route. But in the horrific calculus of slavery, their voyage was a commercial success. During the next five years, Drake and Hawkins completed three more voyages to Guinea, where they captured and enslaved another 1,200 Africans.

By summer of 1568, Drake, only twenty-seven years old, was still part of Hawkins's fleet, but now he was leading eight ships carrying fifty-seven slaves, stolen silver, and jewelry to England, where they hoped to receive a modest profit. On August 12, a storm blew up and walloped the ships for eleven days, scattering the fleet. After weeks of wandering at sea, Hawkins and Drake happened on a Spanish vessel, whose crew told them of a harbor at San Juan de Ulúa. Located near Veracruz, Mexico, this fort was supervised by Spanish bureaucrats who regularly tortured suspects in the dungeons of churches. His worst fears about Catholicism confirmed, Drake recoiled. As Hawkins and the other English captains brought their battered vessels close to the harbor, a large Mexican fleet ensnared them. Only Drake's ship Judith escaped—all the more remarkable because she was unarmed.

Drake spent four grueling months guiding Judith across the Atlantic, arriving at Plymouth on January 20, 1569. Two weeks later, Hawkins limped home to Plymouth, cursing his luck, the Spanish, and Drake, whom he denounced as a deserter. The claim reached the highest levels, and Queen Elizabeth jailed Drake for several weeks to placate Hawkins and to maintain the fiction that she neither condoned nor sponsored piracy.

Drake emerged from captivity seething with resentment—not against the queen, whose tacit approval he needed, or even Hawkins—but against the Spanish, and with good reason. Drake learned that his cousin Robert Barret had been arrested by the Inquisition in Mexico after the governor there, Don Martin Enriques, had given his word that the English adventurers would be safe. The governor then decided there was no need to keep his word when it came to heretics. He took several men prisoner and confined them to a dungeon. Some of the men were forced to renounce their religion while being tortured.

An even worse fate awaited Barret. He was burned at the stake. Drake never forgot and never forgave the outrage. From that time forward he despised Spanish tyranny and saw himself engaged in a crusade against this spreading evil. He had glimpsed their version of a world empire, one based on torture and the exploitation of local tribes, and he was repelled. He renounced slaving and vowed to seek revenge (and his fortune) against those who trafficked in human lives. He became a cunning, enthusiastic pirate, living by his wits, raiding Spanish forts, and taking but not killing Spanish prisoners. He told them he was simply getting back "a bit of his own" for the indignities he had witnessed at San Juan de Ulúa.

The previous circumnavigation came to a tragic conclusion fifty-five years earlier. In 1518, the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan, after repeatedly trying and failing to win support from his own king, Manuel I, persuaded Charles V of rival Spain to back the project. Magellan led a fleet of five little ships and 258 sailors from a variety of nations, many of them risking their lives at sea to avoid prison at home. In a time when it was widely believed that ships could sail over the edge of the world, the armada planned to sail beyond the horizon to the distant Moluccas. There nutmeg, cinnamon, and cloves, among the most valuable crops in the world—more valuable, even, than gold—grew in abundance. European traders wishing to reach the Spice Islands previously had traveled east rather than west, a journey by land and sea, until they reached their goal. A round-trip to the far side of the world lasted seven years or longer, if the traders survived the rigors of long-distance travel. And the herbs they brought back with them to Europe lost considerable potency along the way. Magellan hoped that by going west, in the opposite direction, over water, he would complete the trip in a year or less and return with fresher, more potent spices. All of that was speculation; no one had ever succeeded.

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.