Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

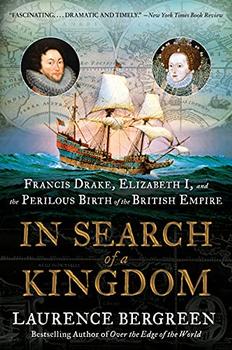

Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire

by Laurence Bergreen

Throughout the voyage, Magellan, equipped with a set of hopelessly inaccurate maps, relied on his navigational instincts to sail from Seville across the Atlantic to the coast of Brazil, all the while fleeing Portuguese ships in pursuit, battling storms, and quelling violent mutinies.

After several disappointments, Magellan located a rumored passage near the southern tip of South America. By this time, he had lost two ships. The three remaining vessels ventured into the passage without benefit of maps. Thirty-eight days later, Magellan spied the Pacific Ocean and wept with joy. His relief did not last long. He faced the largest body of water on the planet, about which almost nothing was known in Europe. On this leg of the journey, his diminished fleet was assailed by storms and menaced by ocean-going warriors in their highly maneuverable proas. Magellan's crew, confined aboard their ships, relied on worm-eaten biscuits and flying fish that landed on the decks. They slowly succumbed to scurvy, which Magellan and other officers escaped by accident. Because of their rank, they were entitled to an allocation of jam made from quince, a tart little fruit rich in vitamin C. Without realizing how or why, those who had access to quince were protected.

By March 6, 1521, the fleet reached the island of Guam, covering a little more than two hundred square miles barely rising above the surface of the ocean: their first sight of land in ninety-nine days. Ten days later Magellan's fleet reached what is now called the Philippines, just four hundred miles from their goal, the Moluccas. They had sailed three-quarters of the way around the world. In the Philippines, Magellan blundered into a confrontation with a combative local chieftain, Lapu Lapu. Feeling secure with their Western firearms and shields and swords, Magellan and eighteen stalwart loyalists squared off against hundreds of warriors charging into harbor, brandishing fired-hardened swords under the command of Lapu Lapu. The men focused their wrath on Magellan, easily identifiable in his gleaming helmet, and cut him down.

After Magellan's violent death, Victoria, laden with precious spices, continued on a westerly course. She was commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano, a Basque navigator, who guided her across the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope, and finally to Seville on September 6, 1522, three years after her departure. The battered ship's arrival astonished the authorities, who had assumed that the entire fleet had come to grief in a remote part of the world. They were not far from wrong. Of the 258 sailors and five ships that had set out, only one ship with eighteen emaciated sailors completed the circumnavigation.

For the next fifty years, Magellan's ill-fated mission was considered a cautionary tale rather than a great step forward in exploration. It demonstrated that circumnavigation was folly, an endeavor for overreaching kings and reckless captains in search of elusive wealth. The Portuguese navigator had established that the world was larger than anyone in Europe imagined—and far more hazardous.

That was how matters stood for more than half a century, when England challenged the Catholic—and Spanish—world order.

At the time of Victoria's return to Seville, Henry VIII had ruled England for thirteen years. His was an exceedingly violent reign. He sent twenty-seven thousand people to their deaths, or nearly one percent of the population of England and Wales. In Germany, Martin Luther, having published his ninety-five Theses, had become the focus of controversy and launched a revolution. In 1520, Pope Leo X, thoroughly corrupt and highly intelligent, issued a bull—an official document—condemning Luther's propositions as heretical. The pope gave the monk 120 days to renounce his Theses, but Luther refused, and on January 3, 1521, the pope excommunicated him. Several months later, on April 17, Luther appeared before the Diet of Worms, in Germany, still defiant, and declared, "Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me." In response, Magellan's onetime sponsor, Charles V of Spain, ordered Luther's writings to be burned.

Excerpted from In Search of a Kingdom by Laurence Bergreen. Copyright © 2021 by Laurence Bergreen. Excerpted by permission of Custom House. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.