Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

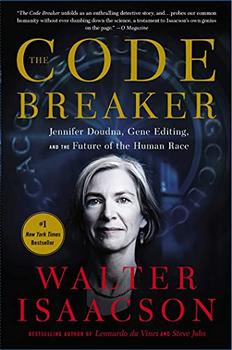

Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race

by Walter Isaacson

Doudna settled on ten projects. She suggested leaders for each and told the others to sort themselves into the teams. They should pair up with someone who would perform the same functions, so that there could be a battlefield promotion system: if any of them were struck by the virus, there would be someone to step in and continue their work. It was the last time they would meet in person. From then on the teams would collaborate by Zoom and Slack.

"I'd like everyone to get started soon," she said. "Really soon."

"Don't worry," one of the participants assured her. "Nobody's got any travel plans."

What none of the participants discussed was a longer-range prospect: using CRISPR to engineer inheritable edits in humans that would make our children, and all of our descendants, less vulnerable to virus infections. These genetic improvements could permanently alter the human race.

"That's in the realm of science fiction," Doudna said dismissively when I raised the topic after the meeting. Yes, I agreed, it's a bit like Brave New World or Gattaca. But as with any good science fiction, elements have already come true. In November 2018, a young Chinese scientist who had been to some of Doudna's gene-editing conferences used CRISPR to edit embryos and remove a gene that produces a receptor for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. It led to the birth of twin girls, the world's first "designer babies."

There was an immediate outburst of awe and then shock. Arms flailed, committees convened. After more than three billion years of evolution of life on this planet, one species (us) had developed the talent and temerity to grab control of its own genetic future. There was a sense that we had crossed the threshold into a whole new age, perhaps a brave new world, like when Adam and Eve bit into the apple or Prometheus snatched fire from the gods.

Our newfound ability to make edits to our genes raises some fascinating questions. Should we edit our species to make us less susceptible to deadly viruses? What a wonderful boon that would be! Right? Should we use gene editing to eliminate dreaded disorders, such as Huntington's, sickle-cell anemia, and cystic fibrosis? That sounds good, too. And what about deafness or blindness? Or being short? Or depressed? Hmmm ... How should we think about that? A few decades from now, if it becomes possible and safe, should we allow parents to enhance the IQ and muscles of their kids? Should we let hem decide eye color? Skin color? Height?

Whoa! Let's pause for a moment before we slide all of the way down this slippery slope. What might that do to the diversity of our societies? If we are no longer subject to a random natural lottery when it comes to our endowments, will it weaken our feelings of empathy and acceptance? If these offerings at the genetic supermarket aren't free (and they won't be), will that greatly increase inequality—and indeed encode it permanently in the human race? Given these issues, should such decisions be left solely to individuals, or should society as a whole have some say? Perhaps we should develop some rules.

By "we" I mean we. All of us, including you and me. Figuring out if and when to edit our genes will be one of the most consequential questions of the twenty-first century, so I thought it would be useful to understand how it's done. Likewise, recurring waves of virus epidemics make it important to understand the life sciences. There's a joy that springs from fathoming how something works, especially when that something is ourselves. Doudna relished that joy, and so can we. That's what this book is about.

The invention of CRISPR and the plague of COVID will hasten our transition to the third great revolution of modern times. These revolutions arose from the discovery, beginning just over a century ago, of the three fundamental kernels of our existence: the atom, the bit, and the gene.

The first half of the twentieth century, beginning with Albert Einstein's 1905 papers on relativity and quantum theory, featured a revolution driven by physics. In the five decades following his miracle year, his theories led to atom bombs and nuclear power, transistors and spaceships, lasers and radar.

Excerpted from The Code Breaker by Walter Isaacson. Copyright © 2021 by Walter Isaacson. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.