Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

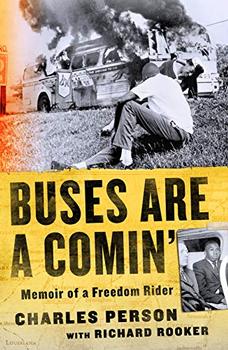

Memoir of a Freedom Rider

by Charles Person, Richard Rooker

Bowlers, in those days, came right from work, so they wore business clothes—long-sleeved white shirts, trousers, and ties. In other words, the clientele at Briarcliff was mostly male. And pinboys—being boys—were male, too. No pingirls at Briarcliff. The customers let us know we were boys in the way they talked to us. Sometimes boy was used as a common noun, as in "I like it when this boy sets my pins. He's good."

Mostly though, it was used as a proper noun, in place of our names.

"Boy, get to work."

"That's the way to do it, Boy."

That felt different, and the older pinboys didn't like it.

"My name's not Boy," they would tell me, "but I can't say anything if I want to keep this job."

I started to think of the way I did not know the kids where Mom worked as a domestic, and they did not know me. I knew their names, and they knew ours, but none of us knew each other in any meaningful way. Mom spent as much time with them as she spent with us, so you might think we would know them the way we knew, say, cousins. But we were no cousins to them, nor they to us. And Mom was no aunt. An aunt would not have her own particular plate and bowl, as Mom told us she had at the home of her employer. They told her these were "special" dishes for her, and Mom pretended to accept that as reasonable. It must have sounded reasonable to them. The dog where Mom served as a domestic had a bowl of its own, too. But not because he was "special." He had his own bowl because he was a dog. It didn't take much for Mom to understand just how "special" her dishes were or why.

As I became aware of my name at Briarcliff and Mom's tableware at work, I began to realize there were two different worlds in Atlanta—defined by color—where we knew of each other and liked each other—at least we said we did. I liked my bowlers, and they liked me; Mom liked her second "family," and they liked her. But they did not care about us, and I was at an age when it was becoming apparent to me they never would. No matter how much the family appreciated Mom mothering their children, she always had her "special" bowl and plate. No matter how much a bowler liked me setting his pins for him, he never saw me as Charles or Tony or Bo. He saw me as Boy.

Mr. O'Neill, the owner, expected us to match the customers in dress, so like them we wore long-sleeved dress shirts buttoned all the way up to our necks and dark slacks. Some even wore suspenders. Our looking our best was important to Mr. O'Neill. I didn't understand why, but it helped prepare me years later when we dressed our best during our protests in the Atlanta Student Movement or on the Freedom Rides so we looked like gentlemen and ladies, not like radicals and reactionaries that society wanted to believe we were. Dress mattered at work. It would mean something on the streets of Atlanta and seats of Greyhound and Trailways, too.

Work at Briarcliff for me started at four in the afternoon following school and went till ten, but we had to wait for Mr. O'Neill to finish the books each night because he took us home in his car. Mr. O'Neill was a good man who cared about his pinboys.

I made friends at Briarcliff. Charles Patterson would be on one side of me; Flu Ellen on the other. Pinboys started off working one lane, but once experienced, we serviced two lanes, so more often than not, Flu, Charles, and I were hopping between lanes and not sitting down on the job. Our first priority after each bowled ball was to protect ourselves from airborne trouble. We dodged and ducked. Hands formed our last line of defense to divert the hurt coming our way. Attentiveness, I learned, was an asset in a pinboy.

Next, we needed to get the ball back to the customer. Fast. We set the ball on its way down the railing by giving it the impetus to make it all the way back. Sometimes we failed to put enough oomph on our return. The ball stopped partway. We'd have to walk up the alley to recover our mistake. That was embarrassing. While the ball returned and the customer prepared for his next roll, we cleared the alley of pins that had not made it into the pit. When a strike was bowled or after the bowlers rolled a second ball, we reset the tenpins. The pins had small holes—short, hollow shafts really—in the bottom of them. Each pit had a lever that pinboys depressed with one foot. That brought ten spikes up from the floor upon which we placed the pins. The spikes identified the proper location for each pin. After resetting the pins, we let up on the lever and either hopped over to the adjacent lane or hopped atop the railing for a moment before the next lane was ready to be reset.

Excerpted from Buses Are a Comin' by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Copyright © 2021 by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A library is a temple unabridged with priceless treasure...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.