Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

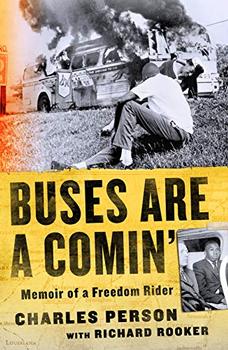

Memoir of a Freedom Rider

by Charles Person, Richard Rooker

"Just the way it is," Flu Ellen told me.

Those students studying at Georgia Tech intrigued me. They came almost every week, and they always came as a group. I never understood how these international students, many of them as dark as me, were allowed to sit down in a Majestic booth, and I was not.

FOOD THAT PLEASES the sign said. It was a relative term.

Just the way it was.

First no Santa. Next, no seat. These awakenings in my life were more like Mom trying to get me out of bed on Saturday morning.

"Why can't I just sleep a little longer?" I'd complain. Then I would roll over for a few minutes more of unconsciousness.

Two subsequent events in my young life startled me right out of bed from the slumber of childhood into asking sociological questions I had never considered. One question was "Why?" The other was "How?"

Let's take "Why?" first. That event happened on a bus. On my way to Briarcliff.

For African Americans in the segregated South, the idea of a startling event happening on a bus was not surprising. Buses represented segregation. Everyone knows that now. Rosa Parks brought that to the country's—even the world's—attention with her defiant act on December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama. What the world learned then, Southerners already knew. The signs made it clear. Whites in front. Blacks in back. In some Southern cities, Negroes paid their fares at the front of the bus, disembarked, walked to the back door, and reentered so as not to "offend" the white folks in front by the mere act of walking past them. Buses in some Southern cities had movable signs. Drivers could move the COLORED sign back a row or two if the white section filled. Moving the sign made more seats available to whites. It also made those behind the sign—that would be us—give up seats. Seats that moments before were perfectly comfortable and perfectly capable of supporting pairs of pants that black men filled or dresses that black women wore, but then, somehow, those seats needed pants and dresses with white skin pressing against the fabric. Peculiar things, bus seats.

Yes, Rosa's singular act taught the world what blacks already knew: We (black human beings) must sit here; they (white human beings) can sit there. Except that Rosa's singular act was not singular. In Montgomery alone, in 1955 alone, teenager Claudette Colvin defied the segregated seating in March—nine months before Rosa did. Mary Louise Smith did the same in October. Many Negros had personal bus stories, often at a young age, that opened their eyes, taught them a lesson, puzzled their minds, and led them toward their awakenings.

Fifteen years before Rosa Parks defied the laws and customs of Montgomery, thirty-year-old Pauli Murray violated the segregation laws of Richmond, Virginia, by refusing to give up her seat in the front of a bus in 1940. When Murray was also denied admittance to Harvard Law School in 1944 because of her gender, she coined the term Jane Crow.2

That same year, on July 6, 1944, exactly one month after D-Day, Lieutenant Jack Robinson found himself in custody at what is now Fort Hood, Texas. The Negro lieutenant objected in strong language and forceful posture when the driver of his bus demanded he vacate his seat next to the light-skinned wife of a fellow African American officer. Military police escorted Robinson off the bus, leading to a general court-martial trial a month later. Had the trial ended in a guilty verdict, the world might never have known the man who became the most important figure in the history of baseball. For Lieutenant Jack Robinson went on to become #42 for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Jackie Robinson.3

Marcelite Jordan Harris, a 1964 Spelman graduate who became the first African American female major general in the US Air Force, grew up in Houston.4 Her bus story happened because she was a young girl who simply followed leadership. To Marcelite and her sister, the driver of a bus was the leader of the bus, so she and her sister wanted to sit right behind the driver—right behind the leader—so they could follow him. When they did that one day—when they sat in the first seat on their city bus—an African American woman in the back came up front and kindly led them to the back where they "belonged."5

Excerpted from Buses Are a Comin' by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Copyright © 2021 by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chance favors only the prepared mind

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.