Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

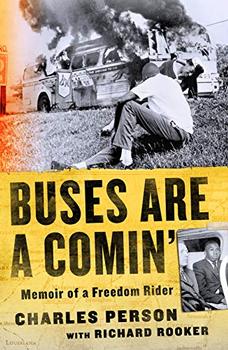

Memoir of a Freedom Rider

by Charles Person, Richard Rooker

Then we found out what Dad was going to do.

"Ruby, I'll take care of it." Dad was a man of few words.

Moments later, as Dad rushed out the door, our shame lingered on our tearstained faces and our sore rear ends. We got our butts spanked. Sometimes I can still feel it today, though I can laugh about it now in a way I could not in 1951.

The Raid on Peach Tree defines the kind of trouble I got into as a youth—the kind of troublemaker I was. That is to say, I wasn't. Mischievous? Misbehaving? Of course. Every youngster is. But troublemaking? I am not built that way. It is not in my DNA.

Strange, then, that a lifetime later—at age eighteen—Atlanta city police locked up me and hundreds of others for the troublemakers we were. Stranger, still, that I could be an "outside agitator" in my native South because I boarded a bus in Washington, D.C., and rode it home.

That is what a segregationist mind can convince itself of: a bus rider is a troublemaker; a native son is an outside agitator. That is what Jim Crow teaches people to believe: that people's "disorderly conduct"—one of the offenses Freedom Riders were charged with—is worthy of their being jailed, beaten, or killed to "teach them a lesson."

Jim Crow. Segregation. These are aberrations from human dignity no one should live under. They should never have existed, but since they did, they should be anachronisms of eras long past. Instead, they are realities conceived from our nation's original sin of slavery, and they continue today in the hearts of those who act to ensure whites remain in charge.

As a young child in 1940s Atlanta, I did not know the existence of segregation any more than a fish knows water. Or a bird air. Or a white child knows whiteness. In my childhood awareness, I wasn't growing up in segregation. I was growing up on Bradley Street—21 Bradley Street.

I was growing up in a community of folks like me in an area of Atlanta called Buttermilk Bottom. Buttermilk because many families there survived on buttermilk and corn bread. Bottom because Heights doesn't make a lot of sense when life lands you in the lows.

In the Bottom, life was simple. I thought my family was wealthy. We weren't. Wealthy in time, food, people, and love? Sure. I had Mom and Dad, my siblings, my cousin Kenneth, and my grandparents Papa and Grandma Booker and Mama Arlena. I had abundance in everything that mattered to me.

It's hard to imagine being richer in food than we were at 21 Bradley. Our relatives lived out in the country, and that gave us access to farm food. Pigs alone gave us delicacies in four seasons. We had bacon all year round but much more than that. Mom used pigs' ears, tails, and feet to make food ranging from meals to snacks. She cooked pigs' ears, put them between two pieces of bread, slapped mustard and hot sauce on them, and I had the best sandwich I ever ate. She cooked pigs' tails down till they were so tender the meat fell off easier than the softest puff of wind disperses dandelion seeds. They were better than dark meat on a chicken drumstick. Mom pickled pigs' feet in vinegar, salt, and pickling spice and let them cure in a canning jar for a month. We had a hard time waiting for what was on the other side of those thirty days.

Mom cured hams in a smokehouse for months preparing for the holidays. The same ham that provided Christmas dinner gave us leftovers for sandwiches and food for breakfast. It also gave us redeye gravy. Mmm, mmm. Mom placed pieces of ham in her cast-iron skillet and browned them on both sides. I watched with "Is it ready yet?" eagerness as she turned the ham over, careful not to burn it, but turn it into a beautiful rich brown. Mom's self-control outmatched my eagerness. After placing the ham on a plate, and sometimes slapping my hand to keep me away from it, she poured leftover coffee into the skillet. The coffee loosened the residue from the pan to make pure magic. My nose knew before my eyes did—breakfast was ready. And I was ready for breakfast. I rushed to my seat, pushed my spoon into my grits, and dug a reservoir for Mom's gravy. She would say, "Tony"—Mom sometimes called me Tony from my middle name, Anthony—"Tony, slow down. Be patient." It was hard for me to be patient. I wanted what I wanted, and I wanted it now. She poured the steaming sauce into the basin I'd created in my bowl and … slapped my hand to keep me away from it. I grabbed one of her piping hot homemade biscuits and placed a piece of the ham inside. Biscuits. Grits. Redeye gravy. Ham. Me. It was Christmas Day all over again every day for a week.

Excerpted from Buses Are a Comin' by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Copyright © 2021 by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.