Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

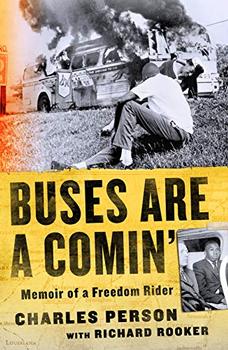

Memoir of a Freedom Rider

by Charles Person, Richard Rooker

Where Papa seemed quiet and serene to me, slow of foot and methodical in his work, Dad was always in a hurry. His hair, brushed straight back and held in place with Royal Crown pomade, formed embedded lines. He would take both hands and sweep his hair backward as his feet moved forward. A cigarette—Pall Mall Red, no filter—constantly hung on his lips and pointed downward as if it were about to fall from his mouth, but the smoke from it seemed to me to be trailing him like smoke from a train. He was on the move because life required it. To make ends meet, Dad needed to be moving forward no matter how far behind he was.

Dad and Mom got married in 1942—the year I was born—and then Dad went off to World War II. So, Dad was away from home even at my birth. More than a million African Americans served a country and a military that did not see them as equal to white Americans. Georgia was the state with the highest percentage of its citizenry enlisted in the war effort. I don't know how Dad knew that, but he took pride in that fact, and it added to his sense of purpose, dignity, and service.

In my teens I came to know that segregation in the army kept Dad behind the front lines. He had signed up to fight. Instead, his unit provided supply and maintenance to those who did the fighting. Learning that put a pang in my heart. I came to know my Raid on Peach Tree adventures with Kenneth were based on the reality of white boys' fathers, not mine. The whipping Dad gave me that day when I was nine was real. My imaginings of Dad's heroism in war were fiction. How much fiction? Maybe Dad cleaned latrines in the war but told me he was a supply officer so he could be bigger in my eyes than in the country's army that made him small.

I hate racism. It even steals your imagination.

As the war moved on to German soil, so did Dad. Dad told us that "kinky hair" fascinated German kids in towns occupied by the Allies. They wanted to touch Dad's hair to see if it was real. Sometimes the Germans wanted to touch black skin to see if it felt the same as theirs. Sometimes they maneuvered around black soldiers to see if they had tails. White Americans were not the only racists on the planet.

These fascinations—kinky hair, the feel of flesh, the possibility of tails—sound bizarre and inappropriate to us today, but the times were bizarre and inappropriate. A German monster tried to capture all of Europe and put it under Aryan rule. That same German devil sought to exterminate an entire race and religion from the European continent.

I think each generation lives in its own bizarreness. That bizarreness makes such perfect sense to the people of that time that the majority live by it, even laugh about it in its time. We make jokes about certain nationalities. We talk in stereotypical voices to diminish those of a different race or sexual orientation from our own. We make insulting gestures mimicking people with disabilities. We snicker when women want to wrestle or box or in earlier times vote. But the bizarreness of any time needs confronting. It needs to be stopped in its tracks. The horror that was Adolf Hitler had to be confronted and stopped. My dad's generation of men walked or drove or got on buses and reported for duty to stand up to it and stop it.

When my time came to confront a bizarreness of my day—the denial of equal access to restaurants, theaters, beaches, voting booths, and public transportation—we walked, we marched, we got on buses, and we reported for duty just as our fathers had. Theirs was a more popular fight even if they were not allowed to fight it.

No, Dad was not present at my birth, and I saw little of him throughout the workweek. Those were the circumstances of his and our lives. On weekends, though, I got some Dad time. He took me fishing, and he taught me how to sit and be quiet. That was hard.

Other weekends Dad took me hiking in the green-capped hills of northern Georgia. Dad loved the outdoors, and he wanted me to love it, too. Usually we walked in Georgia forests full of pine trees and north-Georgia rhododendrons. I'd follow his blue overalls and long-sleeved (even in summer) white shirt up the hills, every now and then stepping on the words Pall Mall to make sure the stub of his cigarette was as out as he thought it was. Little kids take things more seriously than adults do sometimes. Springtime hikes led us through tunnels of rhododendron bushes ablaze in brilliant purple and white. I loved the rare days when I had Dad all to myself.

Excerpted from Buses Are a Comin' by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Copyright © 2021 by Charles Person and Richard Rooker. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The less we know, the longer our explanations.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.