Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Excerpt

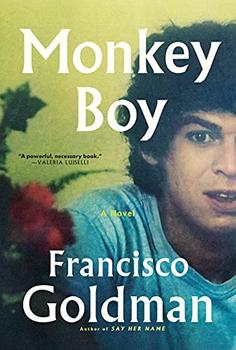

Monkey Boy

All my life, I've been answering some version of the inevitable question: But aren't you Jewish? (Weren't you just introduced to me as Frank Goldberg? Then what do you mean that you were baptized in that church?) I'm half-Jewish, I've always answered. Usually adding: My mother is Catholic. (I'm half-Jewish and half-Catholic I'm sure I used to say as a boy.) Those questions always felt threatening to me; to some degree, they still do. When I answered like I did, did people think I was saying that I was or wasn't Jewish? That's what I'm thinking about, sitting here in this sleek hipster pub that I stopped into after saying goodbye to María and Rebeca at the laundromat and walking around the neighborhood a bit, fuming about Father Blackett, Lexi's arrowhead in my pocket.

When I was a kid, I never would have dared to say out loud: I want to be just one thing, like a normal person is, though I thought it all the time. Having a mother from Guatemala is weird enough, but at least she's Catholic. I'd rather be Catholic because that's more normal. I did know there was some sort of rabbinical law that if the mother isn't Jewish then her children aren't either, but it wasn't a law I ever saw enforced in any way, or that anyone else seemed to know or care about. As a child I did ask my mother to let me go to Sunday School at St. Joe's. But Bert said, Yoli, they'll slaughter him. He can't defend himself against one Gary Sacco, what's going to happen when every goddamned kid is Gary Sacco? Instead, I was put into after-school Hebrew classes. I don't know how Bert didn't foresee what a disaster that was going to be. When two weeks later I just stopped going, not a mote of dust was stirred by query or protest from any quarter.

I want to be nothing. Why can't I just be nothing? What if I'd said that. But what can a fourteen-year-old really know about being nothing?

Nada us our nada as we nada our nadas. But there's no Nada IPA on the menu, so I tentatively order the Spaceman IPA. The waitress, tall and trim in all black, reassures me that I've made a good choice. I order a grilled fontina and guanciale sandwich, too. She brings the beer, and I silently toast and drink to nada.

Up to fifth grade, Mamita always took us back to Guatemala City for the summers, and even though they were supposed to be our vacation months, we were always put in schools. For a few of those summers I was enrolled in the Colegio Ann Hunt. Ann Hunt was an expat from Alabama, and her husband, Scobie, owned travel agencies and tourist hotels. It was at the Colegio Ann Hunt that I encountered for the first time, in the school library, the phenomena of strictly classifying writers by ethnicity and race. The shelves labeled "American" held books by writers from Alcott to Wolfe. The bottom shelves, inches above the floor, of two adjoining bookcases were labeled "Negro," Baldwin to Wright, and "Jewish," Bellow to Wouk, the lower parts of those book spines scuzzy with the dust of broom sweepings. Latino/Latina, or Hispanic, or however Ann Hunt might have labeled it, weren't on her map yet, and neither were Asian, Native American, etcetera. But now I know that Ann Hunt was a pioneer of the American multicultural book business, however inadvertently. She should have gotten a medal.

"In a hyper capitalist society like this one, this commodification of ethnicity and race is both inevitable and good business, much better than just dispersing these writers like multi-colored sprinkles into our more established commercial batters, but you do have to be clear about what you're selling. Somebody buying a novel in our coveted Guatemalan- American niche doesn't want to be surprised to find a bunch of Jews and half-Jews in there." I didn't foresee, when I published my first short stories, how easy I could have made things for myself by publishing under my mother's maiden name, Montejo, as other writers in situations the same as mine have done. Then I thought that as I'd already published under Goldberg, altering it would be shameful, as if admitting it bothered me to be thought of as only Jewish. I was jealous of Jewish writers and half Jews whose last names didn't sound Jewish, all those Millers and Bakers, Mailer, Salinger, and Proust. Or writers who simply changed their name and paid no price in shame or ridicule, James Horowitz to James Salter, who said he hadn't wanted to be typecast as "another Jewish writer from New York." Could it really be possible that Frank Gehry would have had fewer important architectural commissions if he'd kept his name, Frank Goldberg?

Excerpted from Monkey Boy © 2021 by Francisco Goldman. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

Be careful about reading health books. You may die of a misprint.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.