Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

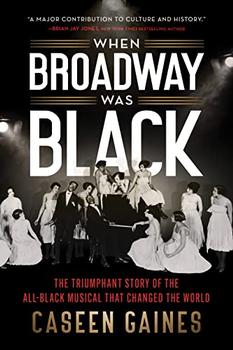

The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World (aka Footnotes)

by Caseen Gaines

The incident that left the most lasting impact on Miller involved Louis Wright, a nineteen-year- old performing with the Richard and Pringle Georgia Minstrels, who was lynched by a mob of masked men. Miller had seen the group on one of their excursions through Tennessee and took special notice whenever he saw them mentioned in the paper. When he heard about what had transpired on the evening of February 12, 1902, when the performers were playing New Madrid, Missouri, he was shaken to his core. As the minstrels paraded into town past the courthouse, two white men—Richard Mott and Thomas Waters—began throwing snowballs in their direction. It was reported that Wright cursed at them, but crisis was averted when the town marshal arrived and deescalated the situation, sending everyone on their way. At that evening's performance, a group of white guys sat in front of the stage, looking for trouble. They heckled the acts, eventually provoking the colored performers to the point where they responded with witty comebacks from the stage. But the interjectors refused to let up. During ballads, they laughed; during comedy routines, they groaned; and when the other white patrons tried to quiet them down, they ignored them.

When the show was over and the house started emptying out, the men took to the stage, demanding an apology from the Black boy who shouted at them during the parade earlier. As they started toward a corridor leading backstage, one of the minstrels drew a revolver and opened fire. Shots broke out in all directions, from both the performers and the white men, and in the pandemonium, several audience members were struck or nearly missed. Five of the minstrels were arrested—while the white men were all free to leave—and later that evening, a group of masked individuals showed up at the local jail, demanding the keys to the cell that housed the entertainers. The prisoners pleaded to be left alone, but Louis Wright was taken into the mob's custody and brought to a large elm tree near the railroad tracks. The sheriff cut his dead body loose the next day.

Flournoy Miller was mortified by what had happened to Wright, but when he met Aubrey Lyles the following year, any doubts he had about his chosen career fell to the wayside. Lyles was also from Tennessee, over two hundred miles away from South Pittsburg in Jackson, a city that had already established a legacy of being outwardly hostile toward Negroes. His father was a musician who hoped to lead an orchestra one day, but he died with his goal unmet when Aubrey was just a boy. Lyles's mother remarried and maintained a modest home, and he and his siblings grew up determined to make something of themselves. He enrolled in Fisk University in Nashville before it was designated as a historically Black university, where he was working toward becoming a doctor, but once he met F. E. Miller, a charismatic upperclassman studying to be an Episcopal minister who had aspirations of a career in entertainment, he caught the acting bug.

The two hit it off right away and developed a comedy routine, which they performed on campus and at the local YMCA, capitalizing on their physical and vocal dissimilarity. Miller was five foot ten, average height, but when put next to Lyles's barely five-foot frame, he looked like a giant. And even better yet, they each sounded like their voice belonged in their partner's body, with FE's measured and gentle while his partner squawked. The centerpiece of their act was an onstage boxing match. Miller would stretch his arm and put his gloved hand on his partner's head while Lyles swung mightily, flailing about in a futile attempt to strike a body blow. They had a clear gift for comic timing and delivery, and their classmates encouraged them to write more bits and keep up the act. Their first taste of monetary success came when they generated $300 from their performances—equivalent to over $6,300 a hundred years later—which they donated toward the construction of a new science building on campus. The school repaid their generosity by placing their names on a plaque outside the hall, but they were hungry for more notoriety. They withdrew from Fisk shortly thereafter.

Excerpted from When Broadway Was Black by Caseen Gaines. Copyright © 2021 by Caseen Gaines. Excerpted by permission of Sourcebooks. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

When first published in hardcover in 2021, this book was titled Footnotes: The Black Artists Who Rewrote the Rules of the Great White Way. In paperback, it was renamed, When Broadway Was Black: The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World. The reviews below were written ahead of the hardcover edition being published, and thus refer to Footnotes.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.