Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

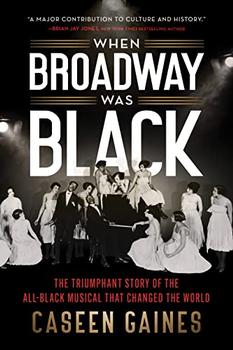

The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World (aka Footnotes)

by Caseen Gaines

Immediately after leaving the university, the two realized that fame and fortune wouldn't come easily. Their first job was with John Robinson's famous touring circus, where they both performed a soft-shoe dance, and thanks to his diminutive size, Lyles also rode a bucking mule. The amateur jockey didn't mind the additional performing responsibilities, but when he and Miller were told they'd have to help break down the tents before the circus departed for the next town, Lyles said manual labor wasn't in his job description. He and Miller quit, instead setting their sights on Chicago's South Side, which had a prosperous Black neighborhood—it would affectionately become known as "Bronzeville"—and an emerging African American theater scene.

The two arrived in the Windy City in 1905 and became acquainted with Robert T. Motts, a former saloon owner and gambler who, once he decided to "make a contribution to his race by providing entertainment along more cultural and uplifting lines," built a cabaret. Unfortunately, it had recently been demolished in a fire, but out of the ashes, Motts was planning to erect the world's first Black-owned theater. The comedians wanted in on this new venture and quickly wrote the book for The Man from Bam, which they envisioned as a musical comedy. The entrepreneur loved what he'd read, hired Joe Jordan, his resident pianist at the saloon, to write the score, and The Man from Bam became the premiere production at the Pekin Theatre on March 31, 1906. The production did well, but while Motts wanted Miller and Lyles to write another show, reality soon set in. Lyles met and married Ellamay Wallace while in Chicago, and when work was slow at the Pekin, he left the theater for a job working on the city's railroads.

While his partner was otherwise engaged, Miller began writing a new show, The Mayor of Dixie, which Motts fast-tracked into production. When Irvin Miller came to visit Chicago, he suggested that Flournoy and Lyles play the characters of Steve Jenkins and Sam Peck themselves, two deceitful business partners cheating to beat the other person in a mayoral race. The show's director, J. Ed Green, agreed, and Lyles took a leave from his new job to reunite with his stage partner. The show ran for three weeks to unwavering adoration, helping to put the Pekin on the map. "This little playhouse is increasing in popularity and besides enjoying the support of the Southside colored population, many white people go there for good entertainment distinctly different from any other offered in the city," Variety noted during The Mayor of Dixie's run.

"We felt that we had arrived," Miller recalled. "But when the curtain descended on the final performance, we had the same reaction all showmen have when they see their scenery being taken out so that the following show could be set up. We stood in front of the theater. We saw our names being covered up by the coming attraction. We thought to ourselves, 'Where do we go from here?'" For Lyles, it was back to the railroad while Miller took a job in the Pekin box office, but unbeknownst to them, requests kept coming in for The Mayor of Dixie, prompting Motts to revive it for another brief engagement. One performance was bought out by a number of socialites from Chicago's mansion-filled Gold Coast section, and when Miller and Lyles looked out from the stage at all the cultured white folks in evening gowns and expensive jewelry laughing at their material, they knew they didn't just want to perform—they wanted to do so on Broadway.

Throughout the next two years, they continued writing and sometimes appearing in musical revues and comedies that played major cities. One of their most successful productions was 1907's The Oyster Man, which starred vaudevillian Ernest Hogan, who called himself the "Unbleached American," and had a brief, successful run in New York. The show didn't play on Broadway, but Miller and Lyles had made a significant contribution to Manhattan's growing interest in Black theater, which began in 1896 with A Trip to Coontown, the first all-Black full-length musical comedy. It was essentially a three-act minstrel show, complete with Black actors in both black-and whiteface, watermelon eating, shucking and jiving, and racially stereotypical songs by Bob Cole and Billy Johnson. After brief engagements throughout the East Coast, Coontown became the first African American musical to play in New York City when the show had a short-lived run at the modest Third Avenue Theater in April 1898, far away from the impressive Broadway houses.

Excerpted from When Broadway Was Black by Caseen Gaines. Copyright © 2021 by Caseen Gaines. Excerpted by permission of Sourcebooks. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

When first published in hardcover in 2021, this book was titled Footnotes: The Black Artists Who Rewrote the Rules of the Great White Way. In paperback, it was renamed, When Broadway Was Black: The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World. The reviews below were written ahead of the hardcover edition being published, and thus refer to Footnotes.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.