Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

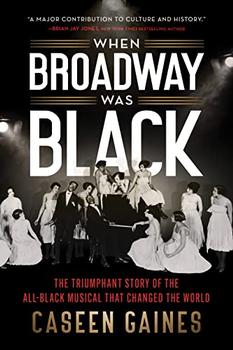

The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World (aka Footnotes)

by Caseen Gaines

Bert Williams and George Walker, the top Black vaudevillian duo who marketed themselves as "the Real Coons," had the most success in elevating the status of Black performers in theater. The two popularized the cakewalk, a high-leg prance created to mimic and parody the pretention of Southern gents and debutants. It became a hit throughout the United States and Europe—the joke was seemingly lost on the white social elite—and in 1898, they starred in Clorindy: The Origin of the Cakewalk, an hour-long one-act musical written by Will Marion Cook, a musician eager to bring the first Negro show to Broadway, and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Clorindy opened on Broadway on July 5 at the top—the rooftop, to be precise—of the Casino Roof Garden theater. It wasn't a Broadway house in the conventional sense, and there was only seating for about 875 people, but the team declared victory nonetheless. "Negroes were at last on Broadway," Cook said, "and there to stay."

Williams, Walker, Cook, and Dunbar scored a proper hit on Broadway when they collaborated again a few years later on 1903's In Dahomey. Jesse A. Shipp Jr., a dynamic writer for Williams and Walker's vaudeville act, directed the show and wrote its book—Dunbar remained Cook's lyricist—which satirized American colonization of African nations. As the show was the first all-Black production to play on Broadway, there were concerns that white audiences would turn hostile, and anxieties were high on opening night. "A thundercloud has been gathering of late in the faces of the established Broadway managers," a journalist wrote in the New York Times following its Manhattan debut. "Since it was announced that Williams and Walker, with their all-negro musical comedy, In Dahomey, were booked to appear at the New York Theatre, there have been times when the trouble-breeders have foreboded a race war. But all went merrily last night."

In Dahomey ran for a respectable fifty-three performances before touring the United States and United Kingdom, paving the way for two more Williams and Walker musicals on Broadway: 1906's Abyssinia, which entertained for forty-eight performances and introduced the self-deprecating "Nobody," which became Williams's signature number, and 1908's Bandanna Land, which played eighty-nine performances. Throughout their decade-long tenure on Broadway, the team demonstrated that Black artists were just as worthy of playing legitimate houses as their white counterparts.

However, just as quickly as all-Black musicals caught fire, they began to disappear from major New York theaters due to a number of factors. George Walker became ill in 1909 during a post-Broadway tour of Bandanna Land, which forced him into early retirement. He would ultimately die from syphilis two years later. While Williams continued without him, starring in the musical Mr. Lode of Koal later that year, he failed to replicate their previous successes. Its run ended during its pre-Broadway tryout, and that same year, the Black theater community also suffered the loss of The Oyster Man's Ernest Hogan. The New York Age evaluated the ever-whitening state of Broadway in a 1910 editorial: "In speaking of the colored theatrical situation as it exists to-day one can, with apologies to the weather forecaster, without hesitation use the familiar term 'cloudy and unsettled,'" they said. "It has been a long, long time since conditions have such been a deep indigo hue."

Coincidentally, as Blacks were becoming but a faint memory on Broadway, Manhattan's theater district garnered a new nickname. Each night, Midtown was bathed in bright lights, thanks to the ubiquitous trend of electric bulbs being used to shine the names of the shows and stars currently playing. By 1910, Broadway was regularly being referred to by its new moniker, the Great White Way.

While opportunities on Broadway had become nonexistent for African Americans, Miller and Lyles were undeterred in their mission to play there. They believed their best approach was to develop their own vaudeville act, as all the Black Broadway stars had done before them, except they would have the added benefit of having written their own material. By the end of the decade, enterprising entrepreneurs were capitalizing on the public's desire for live entertainment by converting storefront shops into nickelodeons, crude performing spaces with little more than a small platform to serve as a stage and a few hundred seats crammed in. There were no fancy amenities for the talent, like dressing rooms or even a backstage; the acts on the bill had to sit in the front row and wait their turn to step onto the makeshift podium and do their few minutes.

Excerpted from When Broadway Was Black by Caseen Gaines. Copyright © 2021 by Caseen Gaines. Excerpted by permission of Sourcebooks. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

When first published in hardcover in 2021, this book was titled Footnotes: The Black Artists Who Rewrote the Rules of the Great White Way. In paperback, it was renamed, When Broadway Was Black: The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World. The reviews below were written ahead of the hardcover edition being published, and thus refer to Footnotes.

There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are either well written or badly written. That is all.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.