Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

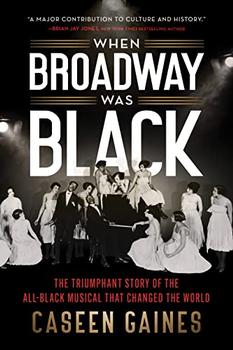

The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World (aka Footnotes)

by Caseen Gaines

While blackface was created by whites for their own gratification, by 1840, African American performers were getting into the act too, darkening their already colored skin for comedic effect. While history would look on these artists with derision, by entering the minstrelsy arena, they were asserting a power and privilege that leveled the playing field. Why should their white competitors have free rein to make a buck, and at Black folks' expense no less? The African Americans beneath the cork often claimed to be recently freed slaves, a marketing tactic more than anything else, which made them more desirable to white audiences eager to see an "authentic" Negro performance. But Black minstrels' material was just as rife with stereotypes as that of their white counterparts, complicating and polarizing their relationship with the Black community. On one hand, they were validating white people's worst perceptions and fears, but on the other, they were showcasing and monetizing their genuine artistic abilities and giving white minstrels a run for their money in the process. This was a vital step in Blacks gaining representation in all-white spaces. Frederick Douglass, who despised the practice of blackface, explained this dichotomy in 1849 when he conceded that "it is something to be gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience."

After an eight-week tour playing dodgy venues throughout Chicago for $40 a week, Miller and Lyles met Harry Weber, a better-connected agent who booked them at the city's Majestic Theatre, the best vaudeville house in the Midwest. After seven years together, the duo had finally become overnight sensations. "We were the first 'talking act' on the big time," Miller claimed. "Up until then, the public had been trained to expect nothing but singing and dancing from Negroes on the stage. Officials of the Keith circuit were afraid that the white public would not listen to such an act. So although we performed as blackfaced comedians, we had to create the illusion that we were white.

"We wore wigs so that the audience might think we were white men," he continued. "I was careful to let my skin show between my gloved hands and shirt cuff to further help the illusion. Finally, however, the wigs became a nuisance in our boxing act and once, after they had fallen off, we decided not to wear them again. In the meantime, so many inquiries had been made as to whether we were white or colored, and our reputation had been so established, that we were not molested after we had stopped trying to pass for white in blackface."

They played consistently on the highly coveted Keith circuit of vaudeville theaters, and because theater remained their first love and ultimate goal, they took a brief hiatus from vaudeville in 1912 to appear in The Charity Girl, an integrated musical comedy by Edward Henry Peple, a white playwright who didn't shy away from dialectical humor at the expense of Black folks. Miller joined the show thinking about Broadway, but once production was underway, his attention turned to Bessie Oliver, one of the chorines in the cast. They married in New York the following year, where she picked up work as a domestic while he continued on the circuit with Lyles. A daughter, Olivette, soon followed.

After over a decade pursuing Broadway together, Miller and Lyles finally hit the jackpot when they were tapped to star in 1915's Darkydom, a highly anticipated musical that Lester Walton, the show's main producer, declared would usher in "a new era for the colored musical show, which has not enjoyed the widespread popularity of former years since the passing away of the Williams and Walker, Cole and Johnson, and Ernest Hogan Companies." As the most celebrated vaudeville comedians of the day, Miller and Lyles were clearly the heirs apparent to help bring Black folks back to the heart of Manhattan's theater district. Not only were they asked to lead the expansive company, but they were able to play Steve Jenkins and Sam Peck, the characters they debuted in The Mayor of Dixie. There was only one thing left to work out: Where do we sign?

Excerpted from When Broadway Was Black by Caseen Gaines. Copyright © 2021 by Caseen Gaines. Excerpted by permission of Sourcebooks. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

When first published in hardcover in 2021, this book was titled Footnotes: The Black Artists Who Rewrote the Rules of the Great White Way. In paperback, it was renamed, When Broadway Was Black: The Triumphant Story of the All-Black Musical that Changed the World. The reviews below were written ahead of the hardcover edition being published, and thus refer to Footnotes.

It is a fact of life that any discourse...will always please if it is five minutes shorter than people expect

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.