Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The hope was that the money The Vixen generated might allow us to continue to publish the serious literature for which we were known and respected, and which rarely turned a profit. It was made clear to me that publishing a purely commercial, second-rate novel was a devil's bargain, but we had no choice. It was a bargain and a choice that our director, Warren Landry, was willing to make.

* * *

Perhaps this is the point to say that, at that time, my life seemed to me to have been built upon a series of lies. Not flat-out lies, but lies of omission, withheld information, uncorrected misunderstandings. Many young people feel this way. Some people feel it all their lives.

The first lie was the lie of my name. Simon Putnam wasn't the name of a Jewish guy from Coney Island. It was the name of a Puritan preacher condemning Jewish guys from Coney Island to eternal hellfire and damnation. My father's last name, my last name, was the prank of an immigration official who, on Thanksgiving Day, in honor of the holiday, gave each new arrival—among them my grandfather—the surname of a Mayflower pilgrim. Since then I have met other descendants of immigrants who landed in Boston during the brief tenure of the patriotic customs officer. Brodsky became Bradstreet, Di Palo became Page, Maslin became Mather. Welcome to America!

And Simon? What about Simon? My mother's father's name was Shimon. The translation was imperfect. In the Old Testament, Simon was one of the brothers who tried to murder Joseph.

I hadn't (or maybe I had) intended to compound these misapprehensions by writing what turned out to be my Harvard admissions essay about the great Puritan sermon, Jonathan Edwards's "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," delivered in Massachusetts, in 1741. My English teacher, Miss Singer, assigned us to write about something that moved us. Moved, I assumed, could mean frightened. I wanted to write about Dracula, but my mother paged through my American literature textbook and told me to read the Puritans if I wanted to understand our country.

I wrote about Edwards's faith that God wanted him to terrify his congregation by describing the vengeance that the deity planned to take on the wicked unbelieving Israelites. It seemed unnecessary to mention that I was one of the sinners whom God planned to throw into the fire. I was afraid that my personal relation to the material might appear to skew my reading of this literary masterpiece.

I had no idea that Miss Singer would send my essay to a friend who worked in the Harvard admissions office. Did Harvard know whom they were admitting? Perhaps the committee imagined that Simon Putnam was a lost Puritan lamb, strayed from the flock and stranded in Brooklyn, a lamb they awarded a full scholarship to bring back into the fold. That Simon Putnam, the prodigal Pilgrim son, was a suit I was trying on, a skin I would stretch and struggle to fit, until I realized, with relief, that it never would.

The Holocaust had taught us: No matter what you believed or didn't, the Nazis knew who was Jewish. They will always find us, whoever the next they would be. It was not only pointless but wrong—a sin against the six million dead—to deny one's heritage, though my uncle Madison had done a remarkable job of erasing his class, religious, and ethnic background. I tried not to think about the sin I was half committing as I half pretended to come from a family that was nothing like my family, from a place far from Coney Island. If someone asked me if I was Jewish, I would have said yes, but why would anyone ask Simon Putnam, with his Viking-blond hair and blue eyes? My looks were the result of some recessive gene, or, as my mother said, perhaps some Cossack who rode through a great-great-grandmother's village.

* * *

When Harvard ended, in June, I'd returned to Brooklyn without having acquired one useful contact or skill my parents had hoped would be conferred on me, along with my diploma. Another lie of omission: My mother and father were astonished to learn that I had majored in Folklore and Mythology. What kind of subject was that? What had I learned in four years that could be useful to me or anyone else? How could eight semesters of fairy tales prepare me for a career?

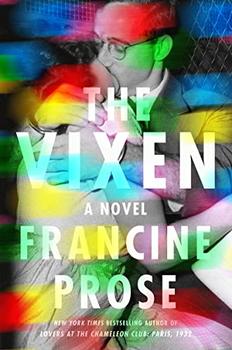

Excerpted from The Vixen by Francine Prose. Copyright © 2021 by Francine Prose. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I have lost all sense of home, having moved about so much. It means to me now only that place where the books are ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.