Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Freshman year, I'd taken Professor Robertson Crowley's popular course, "Mermaids and Talking Reindeer," because it was a funny title and it sounded easy. After a few weeks, I knew that the tales Crowley collected and his theories about them were what I wanted to study. Handed down over generations, these narratives were not only enthralling but also seemed to me to reveal something deep and mysterious about experience, about nature, about our species, about what it meant to tell a story—what it meant to be human. I wanted to know what Crowley knew, though I wasn't brave or hardy enough to live among the reindeer herders, shamans, and cave-dwelling witches who'd been his informants. I wanted to be like Crowley more than I wanted to sit on the Supreme Court or win the Nobel Prize or do any of the things my parents dreamed I might do.

Despite everything I have learned since, I can still remember my excitement as I listened to Crowley's lectures. I felt that I was hearing the answer to a question that I hadn't known enough to ask. That feeling was a little like falling in love, though, never having fallen in love, I didn't recognize the emotions that went with it.

By the time I took his class, Crowley was too old for adventure travel. He'd become a kind of Ivy League shaman. Later, he would become the academic guru for Timothy Leary and the LSD experimenters, and soon after that he was encouraged to retire.

Every Thursday morning, the long-white-haired, trim-white-bearded Crowley stood at the bottom of the amphitheater and, with his eyes squeezed shut, told us folktales in the stentorian tones of an Old Testament prophet. Many of these stories have stayed with me, stories about babies cursed at birth, brides turned into foxes, children raised by forest animals. Most were tales of deception, insult, and vengeance. Crowley told story after story, barely pausing between them. I loved the wildness, the plot turns, the delicate balance between the predictable and the surprising. I took elaborate notes.

I had found my direction.

At the start of the second lecture, Crowley told us, "The most important and overlooked difference between people and animals is the desire for revenge. Lions kill when they're hungry, not to carry out some ancient blood feud that none of the lions can remember."

He kept returning to the idea that revenge was an essential part of what makes us human. Lying went along with it, rooted deep in our psyches. He ran through lists of wily tricksters—Coyote, Scorpion, Fox—and of heroes, like Odysseus, who disguise themselves and cleverly deflect the enemy's questions.

It was unsettling to take a course called "Mermaids and Talking Reindeer" that should have been called "Lying and Revenge." But after a few academic guru for Timothy Leary and the LSD experimenters, and soon after that he was encouraged to retire.

Every Thursday morning, the long-white-haired, trim-white-bearded Crowley stood at the bottom of the amphitheater and, with his eyes squeezed shut, told us folktales in the stentorian tones of an Old Testament prophet. Many of these stories have stayed with me, stories about babies cursed at birth, brides turned into foxes, children raised by forest animals. Most were tales of deception, insult, and vengeance. Crowley told story after story, barely pausing between them. I loved the wildness, the plot turns, the delicate balance between the predictable and the surprising. I took elaborate notes.

I had found my direction.

At the start of the second lecture, Crowley told us, "The most important and overlooked difference between people and animals is the desire for revenge. Lions kill when they're hungry, not to carry out some ancient blood feud that none of the lions can remember."

He kept returning to the idea that revenge was an essential part of what makes us human. Lying went along with it, rooted deep in our psyches. He ran through lists of wily tricksters—Coyote, Scorpion, Fox—and of heroes, like Odysseus, who disguise themselves and cleverly deflect the enemy's questions.

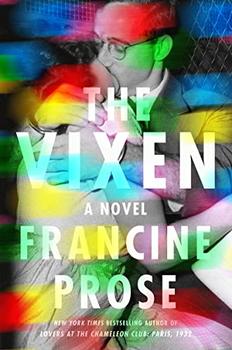

Excerpted from The Vixen by Francine Prose. Copyright © 2021 by Francine Prose. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.