Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

It was unsettling to take a course called "Mermaids and Talking Reindeer" that should have been called "Lying and Revenge." But after a few classes we got used to all the murderous retribution: the reindeer trampling a man who'd killed a fawn, the mermaids drowning the fisherman who'd caught one of their own in his net, the feud between the Albanian sworn virgins and the rapist tribal chieftain. Crowley told so many stories that proved his theories that I began to question what I'd learned from my parents, which was that most human beings, not counting Nazis, sincerely want to be good.

What little I knew about revenge came from noir films and Shakespeare. What would make me want to kill? No one could predict how they'd react when a loved one was threatened or hurt, a home destroyed or stolen. But why would you perpetuate a feud that would doom your great-grandchildren to a future of violence and bloodshed?

I was more familiar with lying. How often had I told my parents that I'd spent the evening studying with my friends when the truth was that we'd ridden the Cyclone, again and again? Lying seemed unavoidable: social lies, little lies, lies of omission and misdirection. I wondered where I would draw the line, what lie I couldn't tell, and I wondered when and how my limits would be tested.

I wrote my final paper for Crowley's course on a tale told by the Swamp Cree nation, about a Windigo, a monster with a sweet tooth and a skeleton made of ice. In revenge for some insult, the Windigo uproots huge trees and tosses them around, killing the animals that the Cree depend on for survival. Finally the people lure the monster to their village with the promise of a cache of honey, and the warriors kill it with copper spears, heated in the fire and thrust into the Windigo's chest, melting its icy heart and bones.

Lying, revenge, the story had everything. I wrote my essay in a fever heat even as I used words I would never normally use, translating myself into a foreign language, the language of academia, clotted with phrases like thus, nevertheless we see, and consequently it would seem, with words like deem, furthermore, and adjudge. The A that I received was my only one that semester, thus further strengthening my desire to study with Robertson Crowley.

At the end of the term, students called on Crowley for individual conferences, and he advised us on what we might want to focus on, at Harvard.

He stood to greet me as I entered his office, deep in the stacks of Widener Library. The furry hangings and snarling wooden masks with bulging eyeballs and bloody incisors reminded me of the mechanical clowns and Cyclops outside the Coney Island dark rides. I was ashamed of myself for recalling something so vulgar in that hallowed place of learning, in the office that I so wanted to be mine someday.

Crowley said, "Mr. Putnam. Good work. While you are at college you must study 'The Burning.'"

"Great idea," I said. "Thank you."

"You're welcome. Now will you please send in the next student?"

I'd watched other students go into his office. Several had stayed much longer. I tried not to dwell on this or to wonder if I'd failed in some way, and if his friendly compliment and his advice were a way of rushing me out. I chose to ignore this distressing memory when, three years later, I asked Crowley for a graduate school recommendation.

Leaving Crowley's office, I'd had no idea what "The Burning" was. It took all my courage to ask his pretty assistant, who later became a respected anthropologist and disappeared in the Guatemalan highlands in the 1980s. I pretended to know what he could have meant, but ...

"Obviously," she said, "Njal's Saga. The only thing he could mean."

I read the saga that summer. When I got to the end, I reread it. The world it portrayed was merciless and violent, but beautiful, like a film or a dream, a world of cold fog rising off the ice, of mists that engulfed you and separated you from your companions. I read other sagas, but I kept going back to that one. Why did I like it best? I wrote my senior thesis about it, as if the answer would emerge if I only read the text more closely and wrote about it at greater length and depth.

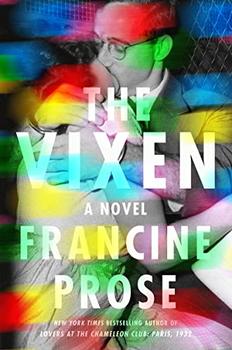

Excerpted from The Vixen by Francine Prose. Copyright © 2021 by Francine Prose. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.