Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

All that time, in secret, my mother was also working hard, working on her brother-in-law, my uncle, the influential literary critic and public intellectual Madison Putnam, who—through his prolific writings, relentless social climbing, strong opinions, quotable bons mots, and eagerness to enter the fray of every literary controversy—had risen above his working-class origins. By the fall, my uncle had secured an entry-level position for me at Landry, Landry and Bartlett.

* * *

By the time I was assigned to edit Vixen, the Patriot, and the Fanatic, I had been at Landry, Landry and Bartlett for six months, much of which I'd spent trying to figure out what I was doing there. Officially, my job as a junior assistant editor involved going through the "slush pile" of unsolicited manuscripts, rejecting hopeful first-time authors and waiting to be fired. The sense that every day could be my last made me feel like the medieval monks who kept skulls on their desks to remind them of their final end.

I liked some things about my job. I liked the free books I could steal from the carts in the hall and from people's offices. I liked reading the modern poets and novelists we published, writers who hadn't been taught at Harvard, many of them European, nearly all of them alive.

I liked the smell of coffee that greeted me in the morning, unlike my coworkers, who ignored me and who seemed to think I wouldn't be there long enough to bother getting to know. After I'd been there for months, they treated me like someone whose name they were embarrassed to have forgotten. They looked past me, or through me, as if I were a ghost, and I began to feel like one, haunting the office. I imagined that my colleagues closed their doors as I walked past them along the labyrinthine corridors, but that would have meant that they were acknowledging my presence.

Only the mailroom guys and the messenger called out, "Hey, Simon!" If my fellow editors were present, they looked surprised, as if they'd seen someone warmly greeting an apparition. Sometimes I imagined that my colleagues were hiding something from me, and later, when my work required hiding something from them, I was grateful for my cloak of invisibility.

I felt lucky to have the job, though it wasn't what I'd planned. I still longed for the library carrel smelling of dust and mold, for the warm dark cave where I could spend my life reading sagas about honor killings, about women with thieves' eyes bringing disaster down on the men who ignored the warnings. Somewhere my authentic self was being acclaimed for his original research, even as my counterfeit self was stuffing envelopes with rejected novels about Elizabethan wenches, aristocratic Southern families with incestuous pasts, the plucky founders of small-town newspapers, and inferior imitations of The Wall, John Hersey's bestselling novel about the Warsaw Ghetto.

On my first day at work, a young woman named Julia, who'd had my job and was leaving because she was pregnant, showed me how to log in submissions and write a two-sentence comment—if, and only if, a stamped self-addressed envelope was enclosed. I was supposed to return each manuscript, gently marred by coffee stains to prove that I had read it, together with the form rejection letter, retyped with a personalized salutation and, if I felt moved, a brief handwritten note at the bottom of the page.

In her soon-to-be-former office, Julia opened the desk drawers and slammed them shut. Then she snapped her hand at the tower of manuscripts stacked against the wall. She hadn't looked at me once. I was sorry that she resented me and sorry for feeling irritated that she didn't try to hide it. It wasn't my fault that she'd been fired. If they hadn't hired me, it would have been someone else.

Under the circumstances, I kept thinking that it was wrong to notice how pretty she was, wrong to be attracted to her haunted, dissatisfied air—to some brave, reckless spirit that I thought I saw in her. I sensed there was something she wanted to say, that she almost said, then decided not to say, something weightier than suggesting I compile a list of adjectives—positive but not too positive—to use and reuse in those scrawled postscripts on the manuscripts I returned.

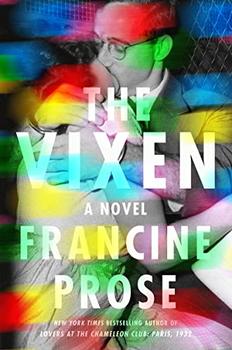

Excerpted from The Vixen by Francine Prose. Copyright © 2021 by Francine Prose. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.