Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Knocking. Someone was knocking on my office door.

I stowed the remains of the chicken sandwich that my mother had so lovingly assembled (dry white meat, white bread, mustard) in the top drawer of my desk just as my boss, Warren Landry, bounded in without knocking again.

Standing in my doorway with his arms braced against both sides, Warren was partly backlit by the low-wattage bulbs in the corridor. He had a Scrooge-like obsession with keeping our electric bills low. His white hair haloed him like a Renaissance apostle, and the costly wool of his dark gray suit gave off a pale luminescent shimmer. He was a few years older than my parents, but he belonged to another species that defied middle age to stay handsome, vital, irresistible to women. I'd spent my first paychecks on a new suit and tie, cheap versions of Warren's, or what I imagined Warren would wear if the world we knew ended and he no longer had any money.

Often, on his way back from lunch, Warren lurched down the hall, all jutting elbows and knees, chatting up the typing pool, leaning on the front desk, stepping into the offices of people he liked.

Sometimes he lost track of who worked where. The worst insult was having him pop in, look at you, blink, shake his head, and pop out.

I was always excited to see Warren, though excited wasn't exactly the word. Petrified was more like it. I was ashamed of my craven desire to interest him, to impress him, even a little. Was it his confidence? His mystique? Or was it simply because he was my boss at a job I'd gotten because of my uncle, who was widely disliked and feared for the power of his journal, American Sketches, which created and ruined careers in politics, literature, and art?

I liked the idea of having a boss. Just saying those two words, my boss, made me feel like a grown-up.

Everyone knew Warren's history. During World War II, he'd gone undercover for the OSS, running a psychological warfare department that spread rumors behind enemy lines. He was responsible for the spread of disinformation warning German soldiers that their wives were cheating on them with draft dodgers and Nazi bureaucrats, inspiring the soldiers to desert and go home and throw the traitors out of their beds.

Shortly after the war he and his Harvard classmate Preston Bartlett III started a small exclusive publishing company in a modest midtown suite. By the time I was hired, the firm's office—divided into spaces ranging from windowless cells like mine to Warren Landry's baronial chambers—occupied half the fourteenth floor of a limestone building with a view (for the lucky ones) of Madison Square Park. I imagined that Warren, always so frugal, must have hired the least expensive architect to design the maze of cubicles, larger offices, and minimal public spaces linked by passages in which, after working there for years, one could still get lost.

Our founders had decided that three surnames sounded more impressive than two. But Warren also liked saying, "I am the one and only Landry!" He said it with a Cheshire cat smile, owning up to his egotism, charmingly but defiantly asserting his right to name two-thirds of a business after himself. Somehow he conveyed his freedom to do whatever he wanted, perhaps because he'd grown up in a warm bath of privilege drawn by servants, a bath cooled somewhat by his contempt for all that privilege meant, which isn't to say that Warren didn't look and act like a very rich white Protestant person.

Preston Bartlett had provided the startup funds and later the fallback money. Unfortunately, the bulk of Preston's fortune now went to the private sanitarium to which he'd been confined since suffering the breakdown that was never mentioned around the office. The firm had taken a hit without Preston on board to make up the deficits and shortfalls.

Meanwhile Warren Landry had become a publishing legend for his persuasiveness, his decisiveness, his impeccable taste, for the boundless energy with which he oversaw the entire process, A to Z. He kept track of the numbers, costs and sales. He'd been known to hand-deliver books when a shipment was late. When a novel appealed to him, he read it in a weekend, though he preferred our nonfiction list: books about Abraham Lincoln, modern Europe, Napoleon, World War I; Calvin Coolidge and Woodrow Wilson, men who could have been, and probably were, Warren's distant cousins.

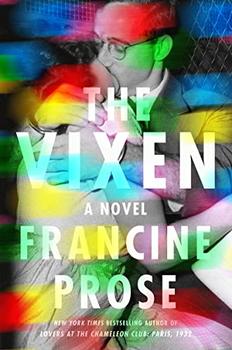

Excerpted from The Vixen by Francine Prose. Copyright © 2021 by Francine Prose. Excerpted by permission of Harper. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Any activity becomes creative when the doer cares about doing it right, or better.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.