Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

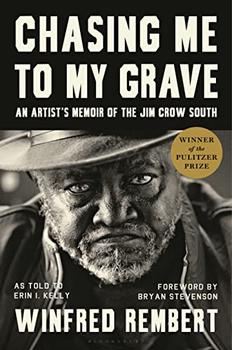

An Artist's Memoir of the Jim Crow South

by Winfred Rembert

Later on, at the meetings, people talked about Americus. Americus was a tough one. They had this terrible sheriff named Fred Chappell. He was a mean monster. He was above the law. He was the law. He was worse than Bull Connor, the commissioner of public safety in Birmingham who attacked the Freedom Riders. This guy wouldn't bend. This sheriff was kicking Black folks' butts every chance he got, hitting them upside the head with his nightstick and giving orders to turn the fire hose on. Back then they would deputize just anybody that was White and give them a badge, and I'd be willing to bet that some of those people wearing the badge and turning on the hose were Ku Klux Klan.

I heard about the demonstrations in Americus in the early days of the Americus movement, and sometimes I would ride over there in a car with guys from Cuthbert and we would sit around in a place on Cotton Avenue called the Bryant Pool Hall. We would play pool and listen to people talk about strategy and what was happening. In 1962, SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) started a voter registration drive. Americus had a population of 13,000. Over half of the people were Black, but there were only 300 Black people on the voting rolls. Sam Mahone was a high school student at the time. I didn't know him back then. I met him in Albany in 2010. He talks about how he escorted people to the courthouse to register.

One day, when he was 17 years old, he took ten people down to the courthouse. Sam was standing across the hallway from the registrar's office, waiting until each person had a chance to register, when Sheriff Chappell attacked him from behind. "I didn't hear him coming or anything. He knocked me down, literally, with a fist to the back of my neck. I immediately curled into a fetal position, as we were trained to do, to protect our most vulnerable parts, like our head and our midsection, and he commenced kicking me.

People who witnessed what the sheriff did would go back and tell others what had happened. Some people who were standing in line even left the courthouse without registering. As Sam tells it, "There was intimidation from the moment you walked into the courthouse, not just from the sheriff but all the Whites who held office there. They were just menacing people who came in there. They did not want Black people to vote.

People got arrested for trying to buy tickets at the "White" window of the movie theater. The demonstrations got bigger after that. The police brought in dogs and burned demonstrators with electric cattle prods. After the civil rights bill passed, in 1964, there were confrontations over segregated restaurants and a swimming pool. Some SNCC workers, including Sam Mahone, were beaten with tire irons and baseball bats by a White mob after they were refused service at the Hasty House restaurant.

Now you had a lot of people in Cuthbert who were afraid to demonstrate. They didn't want to jeopardize their families or businesses. They didn't want to take a chance on losing any of that. They would come to the meetings, but they wouldn't go to the marches. And you had this other group that would put their life on the line. It turned out that was the group I fell into. I was a young boy, 19 years old, in 1965. There were 15 to 20 of us ready to go. We got into a big gray bus that looked like it used to be a school bus and we rode to Americus, which was about 45 miles away. We gathered at the Bryant Pool Hall there on Cotton Avenue. Cotton Avenue was a Black street, with all Black businesses—Black clothing stores, Black poolrooms, Black restaurants, Black funeral home. It's the main drag for Black folks who hang out in Americus. It was familiar to me because I frequented the place when I thought I was a good pool player.

People were gathering around there from Americus and every which way, too many people to fit into the poolroom, so some were standing around on Cotton Avenue. The leaders say where we're going to march, and they told us what our strategy was. The strategy was to obey orders—when the authorities say move on, then we move on. We marched from Cotton Avenue down to the main street in Americus. Cotton Avenue ends right at the main street downtown. That's where we went. It was a peaceful demonstration. People carried signs. The police were there, and the fire department, but they didn't intervene. People sang freedom songs like "We Shall Overcome."

Excerpted from Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist's Memoir of the Jim Crow South. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury Publishing. Text copyright © 2021 by Winfred Rembert and Erin I. Kelly. Artwork copyright © 2021 by Winfred Rembert/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.