Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

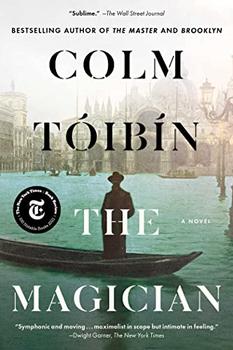

by Colm Toibin

"Our house in Paraty was on the water," Julia would reply. "It was almost part of the water, like a boat. And when night came and we could see the stars, they were bright and low in the sky. Here in the north the stars are high and distant. In Brazil, they are visible like the sun during the day. They are small suns themselves, glittering and close to us, especially those of us who lived near water. My mother said you could sometimes read a book in the upstairs rooms at night because the light from the stars against the water was so clear. And you could not sleep unless you fastened the shutters to keep the brightness out. When I was a girl, the same age as your sisters, I really believed that all the world was like that. The shock on my first night in Lübeck was that I could not see the stars. They were covered over by clouds."

"Tell us about the ship."

"You must go to sleep."

"Tell us the story of all the sugar."

"Tommy, you know the story of the sugar."

"But just a small part again?"

"Well, all the marzipan that is made in Lübeck uses sugar that comes from Brazil. Just as Lübeck is famous for marzipan, Brazil is famous for sugar. So when the good people of Lübeck and their children eat their marzipan on Christmas Eve, little do they know that they are eating a part of Brazil. They are eating sugar that came across the sea just for them."

"Why don't we make our own sugar?"

"You must ask your father that."

Years later, Thomas wondered if his father's decision to marry Julia da Silva-Bruhns, whose mother was reputed to have had in her veins blood from South American Indians, rather than a stolid daughter of one of the local shipping magnates or old trading and banking families, was not the beginning of the decline of the Manns, evidence that a hunger for the richly strange had entered the spirit of the family, which had, up to then, possessed an appetite only for what was upright and certain to yield a steady return.

In Lübeck, Julia was remembered as a small girl arriving with her sister and her three brothers after their mother had died. They were taken care of by an uncle, and they did not, when they appeared first in the city, have a word of German. They were watched suspiciously by figures such as old Frau Overbeck, known for her staunch adherence to the practices of the Reformed Church.

"I saw those children blessing themselves one day as they passed the Marienkirche," she said. "It may be necessary to trade with Brazil, but I know no precedent for a Lübeck burgher marrying a Brazilian, none at all."

Julia, only seventeen at the time of her marriage, gave birth to five children who carried themselves with all the dignity required of the children of the senator, but with an added pride and self-consciousness, and something close to display, which Lübeck had not seen before and which Frau Overbeck and her circle hoped would not become fashionable.

Due to this decision to marry unusually, the senator, eleven years older than his wife, was viewed with a certain awe, as though he had invested in Italian paintings or rare majolica, acquired to satisfy a taste that, up to then, the senator and his antecedents had kept in check.

Before leaving for church on Sunday, the Mann children had to be carefully examined by their father while their mother delayed them by remaining upstairs in her dressing room, trying on hats or changing her shoes. Heinrich and Thomas had to show a good example by maintaining an expression of gravity, while Lula and Carla tried to stand still.

By the time Viktor was born, Julia was less attentive to the strictures that her husband laid down. She liked the girls to have colorful bows and stockings, and she did not object to the boys having longer hair and greater latitude in their comportment.

Julia dressed elegantly for church, often wearing only one color—a gray, for example, or a dark blue, with matching stockings and shoes and the only sign of relief a red or yellow band on her hat. Her husband was known for the precision of the cuts made by his tailor in Hamburg and for his impeccable appearance. The senator changed his shirt every day, sometimes twice a day, and had an extensive wardrobe. His mustache was trimmed in the French manner. In his fastidiousness, he represented the family firm in all its solidity, a century of civic excellence, but in the luxury of his wardrobe he offered his own view that being a Mann in Lübeck meant more than money or trade, it suggested not only sobriety but a considered sense of style.

Excerpted from The Magician by Colm Toibin. Copyright © 2021 by Colm Toibin. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.