Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

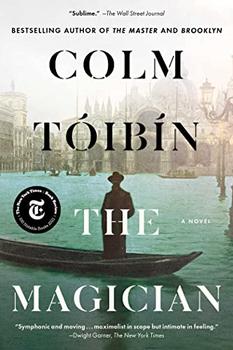

A Novel

by Colm Toibin

To his horror, on the short journey between the Manns' house on Beckergrube and the Marienkirche, Julia often greeted people, gleefully and freely calling out their names, something that had never been done before on a Sunday in the history of Lübeck, further convincing Frau Overbeck and her spinster daughter that Frau Mann was, in her heart at least, still a Catholic.

"She is showy and silly, and that is the mark of a Catholic," Frau Overbeck said. "And that band on her hat is pure frivolity."

In the Marienkirche itself as the wider family assembled, it was noted how pale Julia was, and how oddly alluring her pallor was against her heavy chestnut hair and mysterious eyes, which rested on the preacher in an expression of half-veiled mockery, a mockery that was alien to the seriousness with which her husband's family and their friends treated religious observance.

Thomas realized that his father disliked hearing about his wife's childhood in Brazil, especially if the girls were present. His father, however, loved when Thomas asked him to talk about old Lübeck and to explain how the family firm had grown from modest beginnings in Rostock. His father appeared to derive satisfaction when Thomas, calling at his office on his way home from school, sat and listened about ships and warehouses and banking partners and insurance schemes, and then later remembered what he had been told.

Even distant cousins came to believe that while Heinrich was dreamy and rebellious like his mother and was to be found reading books, young Thomas, alert and grave in his demeanor, was the one who would take the family firm into the next century.

As the girls grew older, all the children would gather in their mother's dressing room if their father had left for his club or for some meeting, and Julia would resume her stories about Brazil, telling of the whiteness of the clothes the people wore there, the amount of washing that was done so that everyone looked special and beautiful, the men as well as the women, the black people as well as the white.

"It was not like Lübeck," she said. "No one saw any need to be solemn. There were no Frau Overbecks pursing their lips. No families like the Esskuchens in perpetual mourning. In Paraty, if you saw three people, then one was talking and the other two were laughing. And they were all in white."

"Were they laughing at a joke?" Heinrich asked.

"Just laughing. That is what they did."

"But laughing at what?"

"Darling, I don't know. But that is what they did. Sometimes at night I can hear that laughter still. It comes in on the wind."

"Can we go to Brazil?" Lula asked.

"I don't think your father wants you to go to Brazil," Julia said.

"But when we are older?" Heinrich asked.

"We can never tell what will happen when we are older," she said. "Perhaps you will be able to go anywhere then. Anywhere!"

"I would like to stay in Lübeck," Thomas said.

"Your father will be happy to hear that," Julia replied.

Thomas lived in a world of his dreams more than his brother Heinrich did, or his mother, or his sisters. Even his discussions with his father about warehouses were further aspects of a fantasy world that often included himself as a Greek god, or as a figure in a story from a nursery rhyme, or the woman in the oil painting that his father had placed on the stairwell, the expression on her face ardent, anxious, expectant. He was not sure sometimes that he was not, in reality, older than Heinrich and stronger, or that he did not go out each day with his father as an equal to the office, or that he was not Matilde, his mother's maid in charge of the dressing room, who took care that his mother's shoes were kept in pairs and that her bottles of perfume were never empty and that her secret things remained in the correct drawers away from his prying eyes.

When he heard them say that he was the one who would shine in the world of business, when he impressed visitors by knowing about consignments due to arrive, and the names of ships and faraway ports, he almost shuddered at the thought that if these people knew who he really was, they would take a different view of him. If they could actually see into his mind and know how much at night and even in the day he allowed himself to become the woman in the painting on the stairwell with all her fervid desires, or someone who moved across the landscape with a sword or with a song, then they would shake their heads in wonder at how cleverly he had fooled them, how cunningly he had won his father's approval, what an imposter and confidence man he was, and how little he could be trusted.

Excerpted from The Magician by Colm Toibin. Copyright © 2021 by Colm Toibin. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.