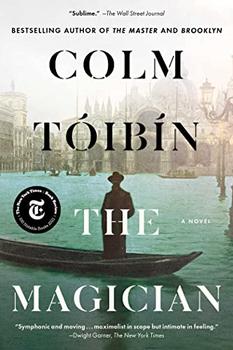

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Colm Toibin

He imagined his mother coming to visit the house on Mengstrasse, when he and his wife would have decorated it, and admiring what they had done, the new piano they had bought, the paintings from Paris, the French furniture.

As Heinrich grew taller, he came to let Thomas know more emphatically that his younger brother's efforts to behave like a Mann were still a pose, a pose whose falsity was increasingly apparent when Thomas began to read more poetry, when he could no longer keep his enthusiasm for culture a secret, and when he would fitfully allow his mother to accompany him on the Bechstein in the drawing room as he played the violin.

Time passed and Thomas's efforts to pretend that he was interested in ships and trade gradually crumbled. While Heinrich had grown defiantly unequivocal in his ambitions, Thomas was nervous and evasive, but still he could not disguise how he had changed.

"Why don't you stop by your father's office anymore?" his mother asked. "He has mentioned it several times."

"I will go there tomorrow," Thomas said.

On the way home from school, however, he thought of the ease he would feel in his own house, finding a place away from everyone, reading his book or just dreaming. He decided that he would go to his father's office later in the week.

Thomas had a memory of a day in that house in Lübeck with his mother at the piano and himself at the violin, when Heinrich appeared in the doorway without warning and stood watching them. As Thomas continued playing, he was alert to Heinrich's presence. They had shared a room for some years, but did not do so anymore.

Heinrich, four years older than he, fairer in complexion, had become a handsome man. That was what Thomas noticed.

Heinrich, who was eighteen then, clearly saw that he was being studied by his younger brother. For one or two seconds, he must also have spotted that the gaze included an element of uneasy desire. The music, Thomas remembered, was slow and undemanding to play, one of Schubert's early pieces for piano and violin, or perhaps even a transcription of a song. His mother's attention was on the sheet music so that she did not take in the way in which her two sons looked at each other. Thomas was not sure that she even knew Heinrich was there. Slowly, as he blushed in embarrassment at what his brother had seen in him, Thomas looked away.

When his brother had gone, Thomas desperately tried to play the violin in time with his mother as though nothing had occurred. Finally, however, they had to stop; he was making too many mistakes for them to carry on.

Nothing like this ever happened again. Heinrich had needed to let him know that he saw into his spirit. That was all. But the memory remained: the room, the light from the long window, his mother at the piano, his own solitude as he stood close to her trying to play, and the music, the soft sounds they made. And then the sudden eye contact. And the return to normality, or something that might have resembled normality were an outsider to have come into the room.

Heinrich was happy to leave school and take up employment in a bookshop in Dresden. In his absence Thomas grew even dreamier. He simply could not apply himself to study or to listen much to teachers. In the background, like some thundering noise, was the ominous idea that he would turn out, once the time came for him to behave like a grown-up, to be no use to anyone.

Instead, he would embody decline. Decline would be in the very sound of the notes he played when he practiced the violin, in the very words when he read a book.

He knew that he was being observed, not just in the family circle, but at school, at church. He loved listening to his mother playing the piano and following her when she went to her boudoir. But he also liked being pointed out on the street, respected as an upright son of the senator. He had soaked up his father's self-importance, but he also had elements of his mother's artistic nature, her whimsicality.

Excerpted from The Magician by Colm Toibin. Copyright © 2021 by Colm Toibin. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

We have to abandon the idea that schooling is something restricted to youth...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.