Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Colm ToibinWhen Thomas observed Heinrich getting ready to accompany his mother to the court where the will was to be read, he wondered why he had not been included. His mother was so preoccupied, however, that he decided not to complain.

"I have always hated being on display here. How barbaric that they will read the will in public! All Lübeck will know our business. And, Heinrich, if you could keep your aunt Elisabeth from trying to link my arm as we leave the court, that would be very kind of you. And if they wish to burn me in the public square after the reading, tell them I will be free at three o'clock."

Thomas wondered who would run the business now. He imagined that his father would have named some prominent men to oversee one or two of the clerks who would look after things until the family decided what to do. At the funeral, he had felt that he was being watched and pointed out as the second son upon whose shoulders a weight of responsibility would now land. He went into his mother's room and looked at himself in the full-length mirror. If he stood sternly, he could easily see himself arriving at his office in the morning, giving instructions to his subordinates. But when he heard the voice of one of his sisters calling him from downstairs, he stepped away from the mirror and felt instantly diminished.

He listened from the top of the stairs when Heinrich and his mother came back.

"He remade that will, to let the world know what he thought of us," Julia said. "And there they all were, the good people of Lübeck. Since they can't burn witches anymore, they take the widows out and humiliate them."

Thomas came down to the hall; he saw that Heinrich was pale. When he caught his brother's eye, he realized that something bad and unexpected had happened.

"Take Tommy into the drawing room and close the door," Julia said, "and tell him what has befallen us. I would play the piano now except that our neighbors would gossip about me. I will go to my room instead. I don't want the details of this will ever mentioned again in my presence. If your aunt Elisabeth has the nerve to call, tell her I am suddenly stricken with grief."

Having shut the door behind them, Heinrich and Thomas started to read the copy of the will that Heinrich had taken from the court.

It was dated, Thomas saw, three months earlier. It began by assigning a guardian to direct the future of the Mann children. Below that, the senator made clear his low opinion of them all.

"As far as possible," he had written, "one should oppose my eldest son's literary inclinations. In my opinion, he lacks the requisite education and knowledge. The basis for his inclination is fantasy and lack of discipline and his inattention to other people, possibly resulting from thoughtlessness."

Heinrich read it out twice, laughing loudly.

"And listen to this," he went on. "This is about you: 'My second son has a good disposition and will adjust to a practical occupation. I can expect that he will be a support for his mother.' So it will be you and your mother. And you will adjust! And who ever thought you had a good disposition? That is another of your disguises."

Heinrich read to him his father's warning against Lula's passionate nature and his suggestion that Carla would be, next to Thomas, a calming element within the family. Of the baby Viktor, the senator wrote: "Often children who are born late develop particularly well. The child has good eyes."

"It gets worse. Listen to this!"

He read aloud in an imitation of a pompous voice.

"?'Towards all the children, my wife should be firm, and keep them all dependent on her. If she should become dubious, she should read King Lear.'?"

"I knew my father was petty-minded," Heinrich said, "but I did not know that he was vindictive."

In a stern and official voice, Heinrich then told his brother the provisions of their father's will. The senator had left instructions that the family firm was to be sold forthwith, and the houses also. Julia was to inherit everything, but two of the most officious men in the public life of Lübeck, men whom she had always viewed as unworthy of her full attention, were designated to make financial decisions for her. Two guardians were also appointed to supervise the upbringing of the children. And the will stipulated that Julia was to report to the thin-lipped Judge August Leverkühn four times a year on how the children were progressing.

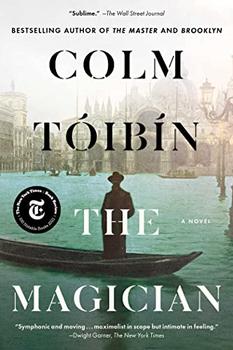

Excerpted from The Magician by Colm Toibin. Copyright © 2021 by Colm Toibin. Excerpted by permission of Scribner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

No pleasure is worth giving up for the sake of two more years in a geriatric home.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.