Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

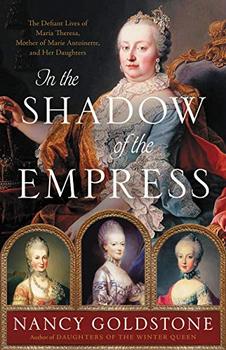

The Defiant Lives of Maria Theresa, Mother of Marie Antoinette, and Her Daughters

by Nancy Goldstone

Her mother, it is true, intimidated her — Maria Theresa was the disciplinarian in the family — but her easygoing father softened the rigor imposed by the empress, and Marie Antoinette worshipped him. On the hot July morning in 1765 that her parents and older siblings left Vienna to travel to Innsbruck in preparation for her brother Leopold's wedding — the younger children, as usual, being left behind — with everyone already ensconced in their carriages ready to go, Francis, much to Maria Theresa's irritation, insisted on holding up the entire procession until nine-year-old Marie Antoinette could be brought out to him for a last tender embrace. "I longed to kiss that child," Francis explained, by way of excuse for the delay. His daughter never saw him again. Her mother returned from that fateful journey a broken, black-clad widow, but the little one would remember this final testament of her father's love for the rest of her life.

For the next two years, like her next-eldest sister, Maria Carolina, with whom she spent most of her time, Marie Antoinette floated just outside the periphery of her mother's attention and so was allowed the freedom of a relatively carefree childhood. These were the days of the lax first governess, whose directives were so effortlessly evaded; of hours spent giggling and pretending with Charlotte; of picnics and playing in the garden. Unlike her clever sister, however, who liked to read and found her lessons tedious because they were too simplistic, Marie Antoinette had neither the discipline nor the aptitude for scholarship. Her attention span was extremely limited; she disliked reading; she had not the focus even to learn to form her letters properly. As her mother demanded to see all of her written schoolwork, this presented a problem until her governess settled upon the happy expedient of first composing Marie Antoinette's papers for her in pencil, after which her disinterested pupil would dutifully trace over the markings in ink.

Then came the fateful autumn of 1767, and with it the death of Maria Josepha and the hurried substitution of Maria Carolina as the sacrificial bride of the puerile king of Naples. By the summer of 1768, Marianne having already gone into the Church, there were only three unmarried archduchesses left in Vienna: twenty-five- year-old Maria Elisabeth (whose Sardinian suitor had backed out due to the rumors of the ravishment of her face), twenty-two-year- old Maria Amalia (still in love with the penniless prince of Zweibrücken), and twelve-year-old Marie Antoinette. And for these three potential brides there were two realms that Maria Theresa was absolutely determined to marry into: Parma, to return the duchy to Austrian interest and thereby recover her inheritance in Italy; and France, to secure the alliance that was the great work of her reign and ensure a lasting peace with what had for centuries been the empire's foremost antagonist.

But as much as she — urged on by Joseph and especially her principal minister, Count Kaunitz (upon whom she relied even more heavily, if that was possible, after Francis's death)— pressed the French for a firm marriage commitment between the dauphin and Marie Antoinette, Louis XV, while not opposing the idea in principle, nonetheless did nothing to promote it, either. Since the death of Madame de Pompadour in 1764, the king of France had become even more indolent, preferring to occupy himself with his new mistress, Madame du Barry, a former streetwalker-turned-courtesan, rather than apply himself to the business of government or foreign policy.

Then, on June 24, 1768, the queen of France, Louis's long-suffering wife of forty-three years, died. She left behind four adult daughters, all of whom deeply resented Madame du Barry. These princesses, having never been espoused, resided at Versailles. Determined to prevent the humiliation of having their father's vulgar, déclassé mistress replace their mother at court, they came up with the happy solution that fifty-eight-year-old Louis XV honor his marital commitment to Austria not by wedding his thirteen-year-old grandson, the dauphin, to Marie Antoinette but rather by taking one of her older sisters as a new wife for himself. When Louis pronounced himself amenable to this option (his one stipulation being that the bride in question be young and beautiful), they suggested Maria Elisabeth, whom they clearly knew only by her pre-smallpox reputation.

Excerpted from In the Shadow of the Empress by Nancy Goldstone . Copyright © 2021 by Nancy Goldstone . Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

A library is thought in cold storage

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.