Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

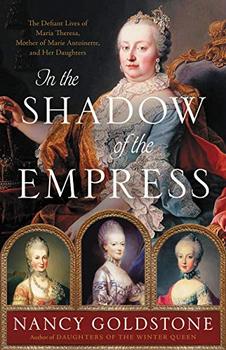

The Defiant Lives of Maria Theresa, Mother of Marie Antoinette, and Her Daughters

by Nancy Goldstone

If this dubious last-minute gambit had succeeded, there is a slim chance (although still very unlikely) that Marie Antoinette might have sidestepped destiny and gone to Parma, where she was exactly the right age and temperament for the duke, and where she could have lived as she liked and been happy, and that Maria Amalia would then have been able to marry for love, as had her sister Maria Christina. But Louis was suspicious and sent a portrait painter to Vienna; the artist confirmed the rumors of Maria Elisabeth's ruined complexion. In a clear win for Madame du Barry, he gave up on the idea of remarriage altogether and instead officially agreed to a wedding between Marie Antoinette and the dauphin. On June 4, 1769, the king of France affirmed the glad tidings to Maria Theresa by means of a personal letter: "Madame my Sister and Cousin," Louis wrote. "I can not delay much longer ... the satisfaction which I feel about the forthcoming union which we are going to form by the marriage of the Archduchess to the Dauphin, my grandson ... This new tie will more and more unite our two houses. If your Majesty approves, I think that the marriage [by proxy] should take place in Vienna

soon after next Easter ... I shall do here what I can, and so will the Dauphin, to make the Archduchess Antoinette happy," he assured her graciously.

And it was at this point that the fates of Maria Theresa's two older unattached daughters were sealed. Having run out of nominees — somebody had to marry the duke of Parma — Maria Amalia, much against her will, was volunteered for the position. To ensure that there was no backsliding, Joseph himself escorted his sister south to Italy, where, on July 19, 1769, she married Isabella of Parma's eighteen-year-old brother, whose maturity was on par with that of his cousin the king of Naples, and who subsequently proceeded to be overshadowed in every way by his unhappy, resentful bride. Maria Elisabeth, sentenced by the rejection of the French king to spinsterhood and ultimately, like Marianne, the Church, was even more distraught than Maria Amalia when the news was broken to her. "She began to sob ... [saying] that all [the others] were established and she alone was left behind and destined to remain alone with the Emperor [ Joseph], which is what she will never do," Maria Theresa confided in consternation to a friend. "We had great difficulty in silencing her."

But maternal distress over her older daughters' wretchedness was

offset by Maria Theresa's satisfaction with her youngest's good fortune. The kingdom of France, home to some 20 million subjects, was considered the apex of eighteenth-century civilization. True, England's navy was the envy of the world, and London might excel at finance and trade, but Paris was universally acknowledged to be the cultural and intellectual center of Europe, and Versailles was still the model for sovereign splendor. Any woman who ascended the throne of France would be responsible for maintaining the exalted prestige of a monarchy that traced its venerable roots to Charlemagne; she would be an object of envy whose deportment would be emulated both at home and abroad. It therefore came as something of a shock to Maria Theresa when, having removed Marie Antoinette from the care of her old governess and assigned her instead, after the departure of Charlotte, to the more accomplished Countess von Lerchenfeld, it was speedily revealed that not only was the thirteen-year-old future dauphine incapable of communicating gracefully in French, but she struggled even to read and write.

There seemed no choice but to cram as much education into her as possible in the short time remaining before her departure for France. Toward this end, Maria Theresa had her daughter sequestered at Schönbrunn Palace along with a gaggle of instructors, including Viennese experts in music and art, as well as a specially imported Parisian ballet master, for Marie Antoinette required coaching in elegant posture, the mechanics of making an entrance and gliding gracefully across a room, and state-of-the-art curtsying. However, even this wasn't considered good enough for the future wife of the dauphin, so Versailles also sent its own tutor, the abbé Vermond, to ensure that the archduchess was properly educated in French history, language, and literature.

Excerpted from In the Shadow of the Empress by Nancy Goldstone . Copyright © 2021 by Nancy Goldstone . Excerpted by permission of Little Brown & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chance favors only the prepared mind

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.